Vøid Contemplation Tactics welcomes our first guest contributor, Rachel Buckmaster-Chamberlin

1991 was a helluva year to turn 18. Now I see it differently: each toe-dip in the water, a new river, each moment, a new life: it’s all a flow. But back then the shifts felt seismic: rare and vivid moments of time standing still while an earthquake below settled all the plates and bones into a new you. I was a recovering prom queen bewildered by my own persistent popularity that was based on being sweet and agreeable, while under the skin I was seething with an anger I still struggle to express. I was already devoted to hard, raucous music - I was studying political science pretty much entirely because of Chuck D, and the class consciousness I was born with was perfectly validated by Fugazi. An outlet for rage at The System, The Establishment, The Entire World? Got it covered, check. But I also felt something deeper and indescribable. The first time I heard Big Black I recognized it immediately, and felt the relief of being understood: Ahh, there it is. The sound of anger at being alive.

This sentiment may come as a surprise if you know me. Or maybe you know Dan and this seems incongruous with your idea of Wife Rachel. Yes, I enjoy life immensely! But the strange, underlying sense of unfairness at not being asked if I wanted to be born has often been dizzying for me, and loud music + good friends + crowded clubs have been key to grounding that disorientation, turning it toward communal experiences rather than paralyzing isolation. And so I begin my tribute1 to Steve Albini.

A necessary point to either remember or try to fathom, depending on your age: In 1991 no “world wide web” meant it was difficult to find a photo of a band, let alone detailed information or cultural context. Musicians (and anyone else) could easily remain a mystery. But the beauty of that was friends gave you music - and music gave you friends. It’s no coincidence that the then-new pal who introduced me to Albini’s music in 1991 remains one of my very closest friends. He was also the one who broke the terrible news of Albini’s unexpected death earlier this May to me. We all found each other this way. After that initial exposure, I started foraging for any scrap of information that I could find about this music I connected with so strongly, and I formed lifelong connections with others who had joined the same search party. And was it ever a party! I’ve talked with many of them these past couple of weeks, all of us stunned and sad and sharpening each other’s dazed memories of our salad days.

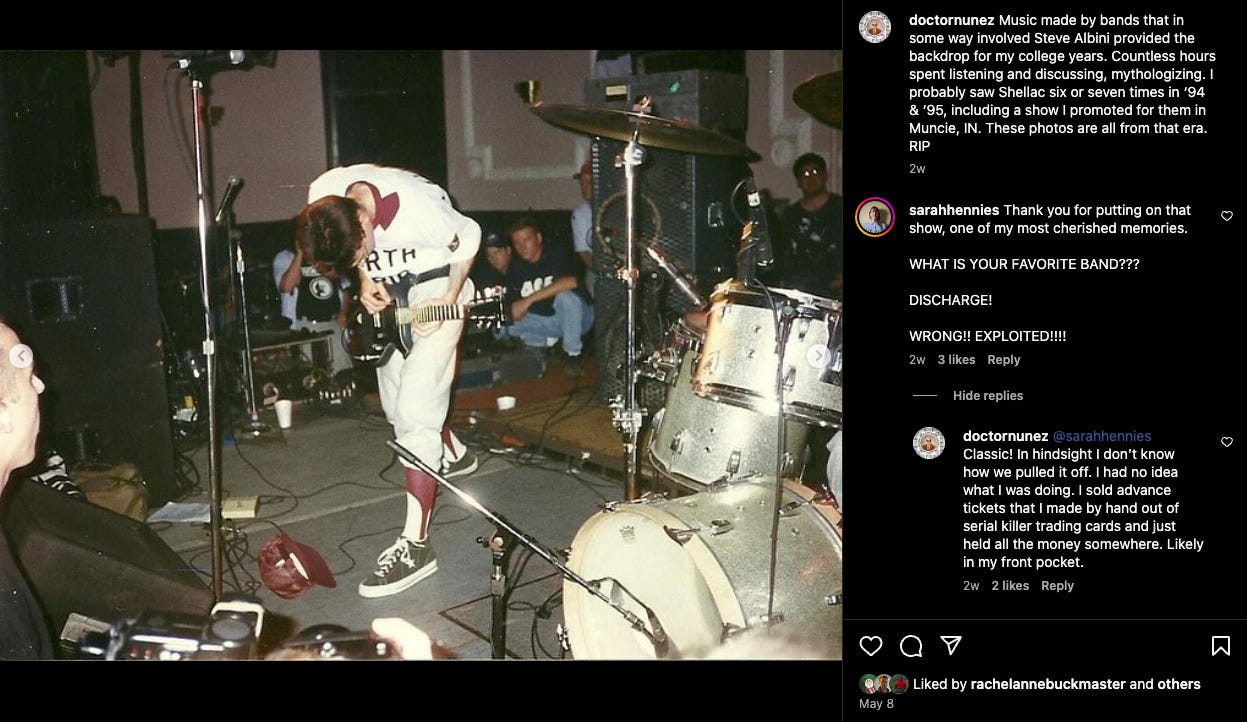

On the phone, via texts and direct messages, Albini’s death became an opportunity to dredge up cherished memories of caffeinated trips to Chicago, the grubby venues in Indianapolis, even a wild show in Muncie. All of them performances that pummeled and pounded our bodies and drove our friendships even deeper. I know cathartic and immersive are overused words in this arena, but here they are apt descriptors: Those shows rattled and consumed our entire bodies. I spent so many of my favorite high-volume shows with closed eyes - Stereolab at the laundromat, Sunn O))) at the chapel, Bell Witch in the old middle school basement. Even as a young person lost in the whirlpool of a Public Enemy crowd, I couldn’t keep them open, physically overwhelmed by the levitating bliss that results from witnessing thunderous live music. But I couldn’t have taken my eyes off Albini if I’d wanted to, ever. Repetitively moving his body in impossible ways, bending in half, throwing his crown toward the sticky floor, he was a scrawny, striking, self-possessed embodiment of their ferocious sound, forcing us to remain grounded, transfixed and human, all of our senses - and old+new friends - taking part in a frenzied synesthesia for one night. My very favorite Shellac memory: seeing them in Minneapolis when they played at the wedding reception of mutual friends, in jeans and tuxedo-graphic t-shirts, absolutely thrashing all of us in an ecstatic, symbiotic celebration of love.

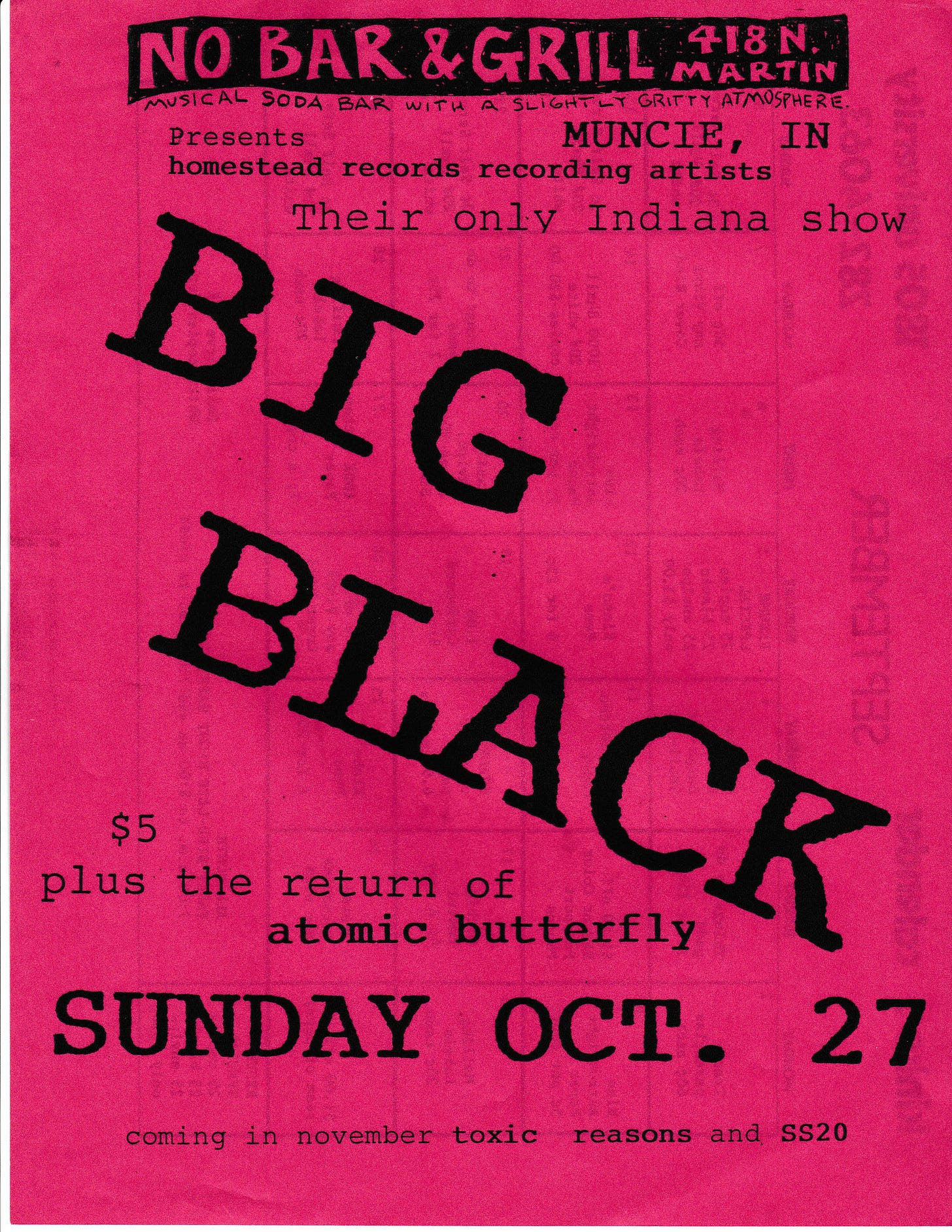

I never saw Big Black. Crushingly and a few years too late, I found out they2 played in Muncie a couple of times when I was in middle/high school. As reported in the local college newspaper on May 19, 1986: “It would be no exaggeration to say they started with a bang. The band tossed a huge handful of firecrackers into the audience before its first song, causing deafening pops, a blare of sparks and room full of thick smoke. This caused most of the crowd to clear out for some fresh air. Incredibly enough, the band kept playing.”

The thought of missing this from a couple of miles away still upsets me, but I’ve processed my disappointment by remembering that I likely spent those evenings hitting play/stop/rewind/play on my yellow walkman and writing down my best guess at Rakim lyrics in the worn spiral notebook every good ‘80s hip-hop kid had. Quite valuable and formative time, in other words, so it’s okay.

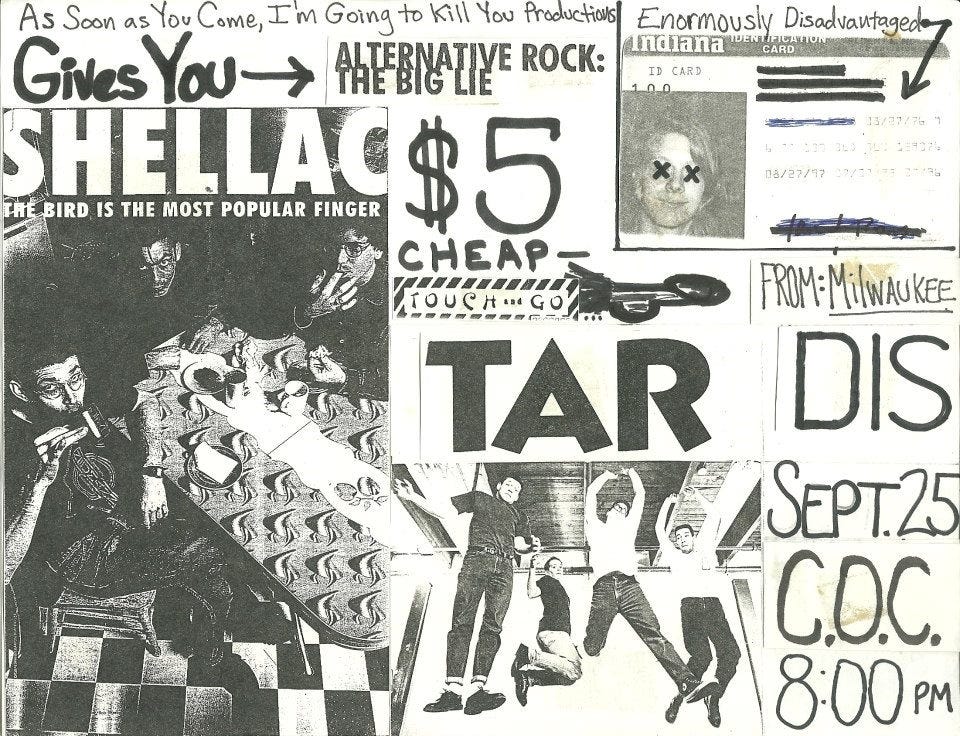

Although I never experienced Big Black live, over a span of 30 years I saw Shellac play more times than I can count - my heart can’t take digging in my box of stubs and flyers and grainy photos quite yet. My second boyfriend – a good friend for life, and the caretaker of an incredible personal archive of punk rock ephemera that proves it all really happened – booked Shellac to play a DIY all-ages spot in downtown Muncie in 1994, a couple of blocks from the current location of Cosmic Chambo Studio. I was too nervous (or maybe starstruck) to be assertive about hanging out behind the scenes with Albini, Trainer, and Weston along with my guy friends, which I have always regretted just a little. But I was still figuring out my place in the scene and, much more difficult, how to claim it.

When I went to see Bikini Kill at the Sitcom – a sublimely dilapidated, tiny all-ages DIY venue in Indianapolis – around the same time, I didn’t realize how much the experience would reveal about the gender politics of our fledgling little punk rock scene. When Kathleen Hanna told the boys to step back and the girls to come forward, literally shouting Girls to the Front: it changed everything. I cringe – lovingly! – remembering the wide-eyed, 19-year old me trying to describe it to my Women’s Studies 101 class the following Monday, and then spending most of the hour weeping. It was an experience that still shapes my understanding of inclusion. The shock of being not just tolerated, but invited to participate is a powerful way to understand exactly how much you’ve been excluded.

Over the years of celebrating that transformative experience, there was another feeling from that night that I didn’t really talk about, one I even struggled to articulate while working through this essay. When I was a girl in front, by direct invitation, the thrill of finally feeling - no, owning - that space was accompanied by the sense of a room full of fuming dudes staring daggers into my back. I was intent on staying put but also afraid to turn around and look, because I knew many of those guys were not just annoyed, but actually furious at being asked to make room for me.

I bring this up because I never caught a whiff of this kind of bullshit macho posturing at Shellac shows. I don’t know how they did it, but despite the band’s aggressive, caustic exterior3, I felt an incredibly inclusive undercurrent to almost everything they did on record, and certainly on stage. People didn’t accidentally4 end up at a Shellac show. If you were there, you weren’t just invited to spectate, you were an integral and necessary part of the performance. I don’t want to claim this was everyone’s experience. But it is a significant distinction for me from a lot of the other shows of that era, and part of why I never related to the “gatekeeper” label Albini often got. He and the other two guys obviously created a deliberately collective vibe, and I left every show knowing I had been an important part of it.

Beyond appreciation for the epic and affirming shows, learning that Albini proudly wore the Midwestern badge and even had an affinity5 for my weirdo hometown delighted me. It made sense, and so did his skewering of the Reagan- (then Clinton-, then etc- etc-) era policies crushing both of us for being broke. I was inspired by his refusal to take money from (or make money for) assholes, so as not to become another asshole with money. Being pissed about a world that not only punishes poor people but actively works to ensure people remain poor is not the same thing as desiring wealth. For all of the hassle and harm and expense one experiences from having relatively little money, I am really grateful I did not grow up wealthy. Albini’s steadfast example of not only resisting greed, but ridiculing the greedy, would’ve made him my hero even if he hadn’t made music I’ll love for a lifetime. He helped me to understand that if being alive is a result of the ultimate lack of agency, leading that life on your own terms is a reclamation of power. For me, loving life is my vengeance, laughter is rebellion, tenderness is defiance, and not wanting more is peace. At some point, I settled into aiming for a simple target, somewhere in between my youthful extremes of people-pleasing and simmering fury. I accepted the most radical ambition of all: to be kind.

Turns out, Albini did too. He made us face the ugliness and hypocrisy and cruelty of life, made us feel it, inescapable and undeniable. And then he said: here, let’s work that brutal shit out together in the sweaty sonic realm - and check it out! What’s left in its place is more room for kindness. And the clarity to be caring and loyal to your friends, always, and fair to everyone else. To shrug off the constant accolades in favor of lifting up other artists at every opportunity. Finding the energy to go all out in decorating your yard for holidays purely to delight the neighborhood kids who have never heard the word edgelord. Get really, really good at something you enjoy, like maybe poker. Start a lovely, low-key Letters to Santa project that you call “the best thing you ever get to do” with your time. Publicly adore and give credit to your partner - for decades. Explain yourself only to those who matter, and then listen to them, too. Hang out with cats and watch all the cooking and woodworking shows in between recording everyone’s favorite records, not caring whether they know it or not. Joke and love and grow and help and vibrate with living - and make your own transcendent noise while you’re at it.

A final note, about that Minneapolis wedding: I had a brief and quiet exchange with Albini at the end of the night. We talked about how beautiful the evening had been, and he told me he planned to keep his boutonniere as a memento of it all. I’m sobbing now with the memory of his gentle sincerity, an all-time favorite keepsake of my own. The bride was (and still is) a gorgeous punk rock girl I fell in love with in 1992 in that Muncie record store basement. And I’ll love her, Albini, and the rest of my own loud life forever.

Rachel Buckmaster lives in Muncie, Indiana.

If you know anyone who might enjoy Vøid Contemplation Tactics please pass it along. It means a lot! Thank you.

Word of mouth is our primary form of promotion. Vøid Contemplation Tactics doesn’t do much on social media, which is good for our mental health. As Dōgen's teacher told him, “You don't have to collect many people like clouds. Sitting with many fake practitioners is inferior to sitting with a few genuine practitioners. Choose a small number of true persons of the way and become friends with them.”

Thank you for lurking anonymously, subscribing for free, or subscribing for money. If you’d like to support this project with a one-time donation, you can also drop some ducats in the tip jar.

I’ll spare you and let the professional cultural critics tackle the complications of his arc, the gold standard reckoning, his ever-increasing openness to growth at a time that none of us realized was so close to the end - I’d only stumble the same way I do when I try to explain my 25-year relationship with Howard Stern.

So did Rapeman, but references to Albini’s lesser known project require more context than a casual name-drop allows, for obvious reasons.

Well, maybe the wine + cheese picnickers at the Millennium Park show in 2009 did, lol.

My first boyfriend was a charming crust punk who lived for a spell in the shower-less basement of our favorite record store - a store that was on Big Black’s Christmas card list because the cranky owner booked them at Muncie’s long-gone but legendary No Bar & Grill and they stayed in touch. And the Big Black Wikipedia page lists Muncie alongside Madison, Minneapolis, and Detroit as a regular tour stop. Crushingly.

Rachel, I loved reading this. It’s a masterpiece. So moving and beautifully written. It ups my Albini knowledge and my music knowledge exponentially (you really should be Yasi Salek’s co-host on Bandsplain), but most of all it deepens my Rachel knowledge. It pulls into focus things about you that I’ve glimpsed and intuited over the years but maybe only ever partially understood until now. I can still remember coming back to Muncie one summer in our college years (probably ‘92?) and, on a visit to the off-campus house you were renting at the time, spying the green-and-red cover of your copy of Big Black’s SaF (can’t remember if it was CD or LP) and having no clue who BB were or how you knew about them. It was a moment, one among many, when I realized that my dear friend Rachel, in addition to being lovely and witty and brilliant and—yes—KIND, was possibly the most fascinating friend I had, with adventurous tastes and an inner wisdom and a cool worldliness that felt so beyond me. That feeling has stayed with me all these years, and it’s one of the (many, many) things I love about you. Thanks for this beautiful piece of writing, friend. (And thanks to Dan for giving it a home.) 💗

love the way this is written, the honest voice and loving rhythm. thank you