This is the first in a series of essays based in part on Zen teacher Joko Beck’s dharma talks about hope.

I.

In March 2012 the Los Angeles-based nonprofit radio station dublab brought Tonalism, a traveling "all night ambient music happening" to the tiny town of Marfa, Texas. I'd recently departed Los Angeles for Marfa, and I was stoked to help old friends coordinate the festival's Chihuahuan Desert debut. The 2012 lineup featured performances from ambient and experimental musicians Sun Araw, M. Geddes Gengras, Matthewdavid, and Houston-based New Age OG JD Emmanuel.

I was getting by in Marfa as a freelance writer and artist. Tonalism coincided with the opening of Ecstatic Camouflage, a solo exhibition of my botanical photography-based work at Marfa Book Co. I was also hosting Inter-Dimensional Music – a weekly mix of underground ambient and classic New Age music – as a volunteer on Marfa Public Radio. And I was in my second year working as a medic with Marfa Emergency Medical Services. My creative practice had gained momentum partially because of the intimate nature of life in a small, remote, and surprisingly expensive town that's also an internationally-renowned artist colony. But responding to 911 calls paid the bills, and I ran up credit card debt when I couldn’t pick up enough shifts on the ambulance.

In the decade since, I left EMS to work in communications and development for arts nonprofits. I eventually left Texas, and lived for a couple years as a resident student at the Indianapolis Zen Center. After that, I got married and moved to an unassuming Rust Belt city in East Central Indiana.

I stayed friendly with the Tonalism crew, continuing to find inspiration in their work, and camaraderie in the conversations that took place in my DMs every couple years. I still produce FM radio as a volunteer, and Inter-Dimensional Music now airs on LOOKOUT FM, dublab's terrestrial network of Los Angeles radio stations, in addition to Marfa Public Radio and WQRT Indianapolis.

NFTs weren't on my radar until Leaving Records – Matthewdavid's wildly experimental “all-genre” label – announced that they were getting into the cryptoart business on Twitter. "NFTs any1?" they asked, and included a link to a confusing and defensive essay from an artist selling NFTs, or non-fungible tokens.

I didn't understand what NFTs were, or why I needed to consider how their carbon footprint compared to that of the cement and chemical processing industries, as the essay suggested. But I was curious because I enjoy Matthewdavid’s music. I often play it on my radio show, and his new song "La Tierra de la Culebra" was an NFT.

Like everyone else who wanted to know about NFTs in Spring 2021, I eventually ended up reading Everest Pipkin's widely-shared article responding to the question “But the environmental issues with cryptoart will be solved soon, right?" I was soon wondering why thoughtful artists that I respected were joining gonzo libertarian investor bros, neo-colonial hipster slumlords, and nihilistic billionaire venture capitalists to be first in line for an experiment that looked so dubious to me and many1 others. Why not at least wait and see?

I was beginning to understand why artists selling NFTs were so defensive though. "The only viable option is total moral rejection," writes Pipkin . . .

Anything less (selling, collecting, posting links to artists selling NFTs, yes even trying to find a less ecologically devastating model) holds up the power of the worst parts of this platform. It grants moral grayzone- an “oh, if my favorite artist is involved, maybe it isn’t so bad?” or a “but I know this person cares for the environment and they participate- maybe they know something I don’t?”

A brief and mostly polite Twitter exchange on the Leaving Records thread followed. Several skeptics echoed my concerns, while an earnest blockchain advocate assured me that this new art market "isn't exclusionary" since "there are 14-18 year olds making millions of dollars." In private correspondence, the conversation was more thoughtful. The question changed from "are NFTs bad or good" to "why are you so passionate about not getting into this space?"

II.

Web3, NFTs, cryptoart, cryptocurrency, Digitally Autonomous Organizations aka DAOs, and the blockchain technology these things rely on are all very confusing. The process of creating the cryptocurrency required to purchase cryptoart – "mining" Bitcoin, Ethereum, Dogecoin, or any of the thousands of lesser-known cryptocurrencies – was described in a now immortalized Tweet as "imagine if keeping your car idling 24/7 produced solved Sudokus you could trade for heroin2."

Critics have repeatedly suggested that it can be hard to understand NFTs because on some level even skeptics expect technology to make sense. If we don’t understand it, we’re probably missing something. As with Theranos, NXIVM, WeWork, Qanon, and LuLaRoe, it’s easier to gain both acolytes and investors when they want to believe. NFTs require faith.

More people started asking questions about cryptoart when the artist Mike Winkelmann sold an NFT at auction for $69 million in March 2021. Now a year later, there are hundreds of articles3 that explain cryptoart and blockchain much better than I ever could. But the reason NFTs started blowing up in the art world seems relatively straightforward. Digital art – mp3s, jpegs, gifs, etc – is inherently reproducible. When you text someone a jpeg from your phone, that jpeg is now on both your phones. Art investors value exclusivity. Artists create scarcity with limited editions. Collectors buy art so they can re-sell it at a profit4. And they stash it away in climate-controlled storage so that nobody can see the art without their permission. NFTs make it seem like you can do that with jpegs, so investors started spending millions of dollars on jpegs.

Except it’s not dollars they’re spending, it’s cryptocurrency, which is a whole other confusing and often sinister thing. One can’t just purchase an NFT via Paypal: You have to buy into cryptocurrency if you want to buy cryptoart. And the very expensive jpeg is still very fungible. The non-fungible token that the buyer owns is a fixed record of a transaction in a digital ledger. Artists who also happen to sell NFTs for a lot of money can argue about this forever in increasingly convoluted ways. Cryptoart critics mostly restate the same basic concept: You’re buying a receipt that says you paid someone for a jpeg.

In February 2021 Artnet offered a similarly concise description of the NFT market as "an easily digestible commercial delivery system" where the art is "stripped from the equation" as platforms "likened to Sotheby's" cater to "nouveau crypto riche" investors who "flip this shit instantaneously."

The problems with NFTs seemed relatively easy to grasp – carbon footprints, hyper-commodification of art by creating artificial scarcity; the right wing talking points that show up in pro-blockchain arguments, radical libertarian subreddits, and anti-semitic conspiracy theories – compared to the solutions.

While looking for pro-blockchain arguments, I kept getting getting hung up on the radical language that tech-utopians were using. It's one thing to say "try this one weird trick to get rich selling jpegs" and another to say you're blazing a trail to liberate digital artists – along with the oppressed peoples of the Global South and humanity in general – from the tyranny of banking regulations.

Cryptoart optimism seemed to fall into two categories: First, there are the wide-eyed soliloquies about empowering “creatives5,” hope that wealthy artists and their patrons will make more charitable donations, faith in carbon offsets, and complaints that criticism stifles innovation.

Then there are the often impenetrable tech-utopian6 explanations of how NFTs, cryptocurrency, and blockchain is all . . . something . . . more than what it appears to be. In the art world, these arguments sometimes avoid the libertarian label, but they often reveal few tangible political positions at all. Instead, lots of enthusiasm about vague concepts like "ownership" and "openness," along with a disdain for financial regulation and peculiar concerns about fiat currency, contracts, and censorship.

Many of these arguments are made in the rhetorical style practiced by billionaire Silicon Valley intellectuals like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen. Aaron Timms describes this kind of thinking in The Baffler:

First, the point of your interventions in the public sphere is not to “win” any “argument,” nor to attract new adherents or convince neutrals of the righteousness of your cause. It is to avoid competition. When competition seeks you out, as it invariably will, your task will be to lose the debate and propose ideas that “seem” (and often are) “shit,” since popular discourse is a test of conventional mindedness; to be truly radical, you must be wrong. Second, there is no absolute moral evil that cannot be playfully reframed on irrelevant grounds as a net historical good.

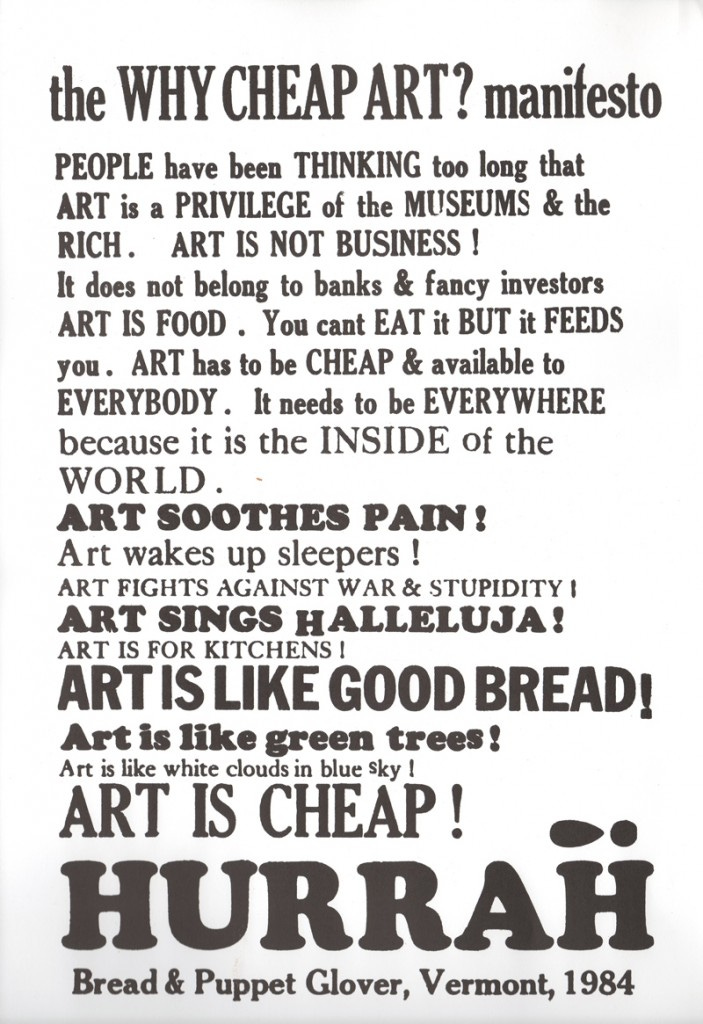

But for my purposes, getting a firm grasp on the technology is beside the point. My answer to the question "why do you think NFTs are probably bad while also admitting that you don’t understand what they are?" is a naive version7 of this cynical contrarianism: I don't want to get rich, acquire power, or create a legacy. I think art should be “like white clouds in blue sky8.”

I'm more interested in the optimism of anthropologist and anarchist activist David Graeber when he writes in Utopia of Rules, that "the world is something we make, and could just as easily make differently." If an artist wants to be counted as part of the broad coalition of people making the world differently, they could start with another of Graeber's ideas: Thinking about human interaction as something more than ledger entries documenting commercial exchange driven by innate self-interest. "When we start from the assumption that human thought is essentially a matter of commercial calculation, that buying and selling are the basis of human society," he writes in Debt: The First 5,000 Years, then "once we begin to think about our relationship with the cosmos, we will necessarily conceive of it in terms of debt."

There's a similar idea in Affirming Faith in Mind, a foundational Zen text written sometime between 600-900CE: "Both gain and loss, and right and wrong / once and for all get rid of them."

NFTs further reduce art to an investment opportunity, albeit one in which digital artists may have more control. But the dominant capitalist power dynamic that is essential to traditional art markets goes unchallenged, and valuation based on the fetishization of exclusivity continues. We don’t create a more equitable world by making more rich people. And as Graeber writes elsewhere, patronage is not about about elevating the artist to the same level as the patron.

Artists hoping that cryptoart will be a radical alternative to the traditional art market remind me of people who came to the Zen Center looking for the secret to happiness, or the people I met on the ambulance who were looking for reassurance that the terrible thing that had just happened can be fixed. They're looking for a fast, easy solution to a problem that doesn't involve sacrifice, discomfort, or letting go of anything.

You don't need to understand the byzantine complexities of decentralized digital ledgers and peer-to-peer networks to catch a vibe. One can at least admit that – paraphrasing a March 2021 editorial by Michael Connor, the artistic director of digital arts nonprofit Rhizome – "so many aspects of cryptocurrency culture boil down to questions of faith."

Or as blockchain critic David Golumbia writes in The Politics of Bitcoin: Software as Right-Wing Extremism9, "hope is a huge part of the problem."

III.

There was an unexpected similarity between working as a medic serving Presidio County, Texas – one of the largest, most sparsely-populated, and poorest counties in the United States – and living at the Indianapolis Zen Center, one of the only Buddhist organizations serving the capital city of a conservative Midwestern state. In both situations, my colleagues were primarily grumpy but essentially kind middle-aged men with close-cropped homemade haircuts. People sought us out when they were in trouble, and our doors were always open. Our duty was to take care of anyone who asked for help, regardless of income level, health insurance coverage, or immigration status. An important part of helping was being honest, and not avoiding the reality of the present moment with comfortable answers and easy assurances.

Life as a medic is rarely depicted as the "long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror" kind of job that it is. I did a lot of cleaning and disinfecting of the ambulance, along with basic home health care for people without access to medical facilities. Even on these welfare-checks, we went in with eyes up, and rarely told patients that "you're going to be okay." We were on scene because things were not okay.

Likewise, zazen – or sitting meditation – is rarely depicted as the sometimes boring, uncomfortable practice that distinguishes it from relaxation techniques or self-help mind hacks. As a Zen Center resident I spent a lot of time enforcing kitchen hygiene, and cleaning up after Fuzzy and Mr. Easy, the temple cats who liked to shit on the meditation mats. And we usually didn't tell troubled visitors that "you're going to be okay." Sitting together in the dharma room, things were already okay.

Hope and faith weren’t required for either experience. "To do this practice, we have to give up hope," the teacher Joko Beck writes in Everyday Zen. "We have to give up this idea in our heads that somehow, if we could only figure it out, there's some way to have this perfect life that is just right for us. Life is the way it is. And only when we begin to give up those maneuvers does life begin to be more satisfactory."

IV.

Like most get-rich-quick schemes, the Los Angeles-based social network slash blogging slash photo-sharing slash music-streaming slash website-building platform where I worked as editor-in-chief in the '00s ran on hope. It was presented by the cofounder on his artist CV as "an experiment in the redistribution of access to media production in the form of a for-profit corporation." Our project was a product of the heady pre-Great Recession era when business writers were enthusiastically proclaiming that "the MFA is the new MBA."

Working there required faith that our sometimes confusing technology and somewhat mercenary approach to ideology would lead to some unspecified utopian end. I was hired to express those aspirations using a fun but nonsensical combination of jargon that I cherry-picked from revolutionary theory, radical metaphysics, and transgressive artists. We promised users the opportunity to become "a swarm of new selves" with free unlimited file storage. I was an early adopter of the Silicon Valley intellectual style.

While we showcased portfolios from freshly-minted MFAs and HD archives of underground film, I also edited pointless celebrity blogs and hastened the death of the good internet by filling our site with language optimized for search engines. The bosses told us that "everything is going to be okay," and in spite of some of the far right political figures and predatory adult entertainment entrepreneurs that I saw taking meetings in our office, I composed rhetoric about remaking the web in exchange for a generous salary and stock options.

When the money ran out after a year or so, the stock options evaporated and the owners sold the URL to what would become the world's most disruptive and exploitative rideshare app. Our work disappeared from online. The only evidence I have of my time there is a print copy of a promotional 'zine that we produced for a trade show.

V.

As a Nationally Registered EMT-Basic in Texas in 2010 I made $11 an hour with no benefits. I had my own cheap health insurance, which could get expensive as an insulin-dependent Type-1 diabetic. I was experiencing firsthand what Graeber describes in Bullshit Jobs as "the inverse relationship between the social value of work and the amount of money one is likely to be paid for it."

After four years of EMS I'd delivered a baby, saved some lives, quit smoking a dozen times, and learned what it looks like when people die unexpectedly. I also learned how hope can blind a person to what's happening in front of them. Hope can make you look away from the present moment, and as a medic one of the most important parts of the job is being fully present for extremely boring, sad, gross, and terrifying moments.

I considered continuing as a first responder by upgrading my certification with a year of paramedic training for an extra $3/hour. Or I could get a job with benefits at the arts organization that was literally across the street from the EMS station. The nonprofit job would almost double my salary, and I no longer had to jump out of bed at 2am because a drunk guy flipped his motorcycle into a ditch and fractured his skull, or one of my neighbors forgot to take their blood pressure meds.

Doing communications and development work for arts nonprofits was a lot like writing for idealistic tech startups. Instead of courting venture capitalists with a salad of words half-remembered from my undergraduate film studies syllabi, I sought the charity of patrons and foundations with a complex and aspirational medley of artspeak and social justice language. The 1400-page copy of J.I. Rodale's Synonym Finder that I'd acquired during my startup tenure was just as useful in discovering obscure alternatives to tech buzzwords like "connectivity" as overused development keywords like "generosity."

The majority of the nonprofit's programming was free to the public. At any given opening there might be an equal percentage of guests who flew in on private jets, and locals who'd gone to bed hungry at least once or twice in the last month. Anyone who’s worked in the art world long enough will be familiar with the cognitive dissonance that comes from describing works of art that serve as conceptual critiques of capitalist violence, brought to you in part by the generous support of individuals and organizations with bank accounts that are representations of the same violence.

"Everything is going to be okay," is what I told myself. We had faith that the ends – arts education programs, installing weird sculptures in our economically depressed region, and hosting symposiums "considering the scale of climate change from the perspective of artistic practice" – would justify the means. "The means" being the further legitimization of the resource extraction companies, arms manufacturers, and non-denominational vampires whose hoarded wealth has always funded the creation of certain kinds of art in capitalist economies. If you believe that billionaires are the problem, and the art world economy that pays for your health insurance is driven by billionaires, then faith is part of the job description.

VI.

My experience as an artist on the other side of the gallery cash register made me just as uncomfortable. After a few more shows, I was frustrated with selling work to collectors that I never met. I felt awkward showing the work to my broke friends with the comparatively modest but still unaffordable $1000 price tags that meant I might break even after the gallery took their cut. When the commercial gallery I was working with refused a series of $100 prints, I offered them for sale in a small show at another space in Marfa. The commercial gallery kicked me out the same day.

The price one sets for access to an art experience is one way of indicating who the art is for. And so I took over an abandoned house and opened a squat gallery, displaying those same canvases next to broken windows, spider webs, and the native ferns that my botanist girlfriend at the time curated in the sink. The South Plateau Adobe Ruin was unsupervised and open 24/7. It was for anyone willing to poke around a ruined adobe on an overgrown lot at the dark end of the street. I posted the rules on the splintered door: "Enter at your own risk, use an inside voice, don’t disturb the wasps, and leave no trace." Outside of a few cigarette butts, everyone cooperated.

I was stoked when Tyler Spurgin, a local artist friend, came by one day and installed a few of his concrete and bone sculptures. But he wasn't asking my permission. "It's not like it's your house," he said. And that was the point.

SPAR was my most successful art project by any measure other than financial gain. Texas arts mag Glasstire even wrote about it as one of the highlights of the 2015 Chinati Weekend extravaganza. When I left Texas, I had the satisfying experience of selling my work to friends for whatever they wanted to pay me, trading it for one of Spurgin's bone and concrete works, and offering it as thanks for help loading the moving truck. If you know where to look for it, Spurgin has since opened another squat gallery called Coming Soon: Starbucks Marfa.

VII.

Many people – myself included – who visit Zen Centers are looking for easy answers. They're in pain, and hoping to learn the secret to avoiding suffering. Zen Centers can be good at dispensing answers that are simultaneously effective, radical, and disappointing. One of the most significant changes in thinking that Zen suggests is to stop hoping that things will change to suit your comfort level. As the teacher Ezra Bayda writes in Beyond Happiness:

We see our discomfort as the problem: yet it’s the belief that we can’t be happy if we’re uncomfortable that is much more of a problem than the discomfort itself. One of the most freeing discoveries of an awareness practice is when we realize firsthand that we can, in fact, experience equanimity even in the midst of discomfort.

This is not what most people want to hear. They want to be a bad ass, to be 10% happier, increase their productivity, heal their DNA, or literally levitate. They hope that meditation and other mindfulness practices will be elixirs that restore mental and physical health without changing anything beyond posture. On some level, most people know that wealth, power, and fame won’t lead to happiness. But rejecting that idea is not the same thing as passing on opportunities to acquire wealth, power, and fame.

It's all the more challenging when the loudest voices in our culture are constantly emphasizing the importance of autonomy, and reminding us that autonomy requires accumulating wealth and power. When we deny our connection with each other and focus on competition for artificially scarce resources, we begin to conceive of ourselves in binary terms, as independent creatures separate from the cosmos. In the disorienting haze of life under unfettered capitalism, it's easy to give up on the idea that "you don't have to fuck people over to survive." We keep fucking people over because the world keeps telling us that it’s the only way to protect ourselves from getting fucked over.

IIX.

While I lived at the Zen Center I became a yin yoga teacher. I started making slow-moving botanical mandala videos as part of the "mindfulness installations" and impermanence-focused yoga sessions that I hosted at house galleries, DIY spaces, organic burial grounds, and metal festivals. I welcome compensation, but thanks to my supportive partner, I'm not trying to pay for insulin with psychedelic death yoga income. And as I learned from countless hardcore shows in my youth, "all ages" and "no one will be turned away for lack of funds" are two ways to make an art experience less exclusive.

Making the decision to prioritize the ephemeral and affordable aspects of both my creative practice and my life has been humbling, frustrating, and frightening, but it gives me more freedom. My partner and I work together to maintain a mellow, sustainable lifestyle rather than focus on ambition or money. She has a secure job working for a public university, and we rent an affordable apartment in an unassuming Midwestern city10 where there are many wonderful people, but there’s not much to do. I stopped making stretched canvases and started printing on fabric because it’s cheaper to produce, and people that I actually know can afford my work. I don’t stress over whether patrons will be offended by my politics, charge exorbitant prices for meditation workshops, or worry if I’m legitimizing newly emergent and possibly unethical art markets. As it says in the Heart Sutra, “. . . also no attainment / with nothing to attain.”

This freedom arises from giving up aspirations toward self-reliance and autonomy. Rejecting the idea of human experience as a series of business transactions means accepting help and offering help without keeping ledgers. It's recognizing that I wouldn't have the privilege of doing these things without allowing myself to be dependent on my partner. It's about accepting and acknowledging a lifetime of support from my family and the scores of friends who've encouraged me, taught me things, purchased my artwork, helped me make rent, and let me live in their basements. Some of that is privilege, but all of it is letting my guard down and not trying to do everything on my own. As I continue to prioritize relationships with friends over investors, patrons, and collectors, the crucial difference between charity and mutual aid becomes increasingly clear.

It's a reminder that change arises as a result of how we live11 as much as from what we create. As social justice facilitator ann maree brown writes in Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, we have an opportunity to "see our own lives and work and relationships as a front line, a first place we can practice justice, liberation, and alignment with each other and the planet.”

IX.

In each of these roles – startup editor, medic, grant writer, Zen Center resident, multidisciplinary psychedelic death yoga artist – I employed the righteous language of liberation. Each mission was undertaken more or less in earnest. But then – as the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis often observes – "something strange happened."

At the startup and the arts nonprofit we claimed that we wanted to change the world, but without challenging the power and ideas that are used to make the world. Appropriating the rhetoric of liberation to make money is not the same thing as working with your curmudgeonly housemates at the Buddhist commune to liberate the dharma room from cat shit before guests arrive for 6:30am meditation practice.

This is putting big effort into hope, and little effort into work. "When I say give up hope, I don't mean to give up effort," Joko Beck writes in Everyday Zen:

"As Zen students we have to work unbelievably hard. But when I say hard, I don't mean straining and effort; it isn't that. What is hard is this choice that we repeatedly have to make. . . We have to sit with pain and we hate it. I don't like it either. But as we patiently just sit our way through . . . we are slowly transformed in this practice. It's not by anything we think, not by something we figure out in our heads. We're transformed by what we do. And what is it that we do? We constantly make that choice. We give up our ego-centered dreams for this reality that we really are."

With Zen and EMS we weren't trying to change the world. There was no hope, only the work of helping people in their experience of life as it is. My work as an artist is considerably less vital, but the motivation is the same.

X.

Tonalism 2012 was a wonderful weekend, but the festival hasn't returned to Marfa since. The "all night" part of the happening didn't take into account the wide-ranging temperatures that result from the Big Bend's high elevation. Once the mixers froze around 2am the remaining half-dozen attendees roused themselves from sleeping-bag cuddle puddles to go home.

Along with Walmart, Taco Bell, Jack Dorsey, Aphex Twin, and at least one reality TV star who was previously selling “farts in jars,” Leaving Records continues to sell NFTs. In 2021, Matthewdavid's two-minute “La Tierra de la Culebra'' sold for 1.5WETH, a cryptocurrency that was roughly equivalent to $3,000 USD at the time of the sale. As of this writing in mid-January 2022, its value had increased to nearly $5,000. You can also download a lossless audio file from Bandcamp for $1.50.

The label has its own currency now – $GENRE – and an associated DAO12. Leaving’s currency can be used to buy NFTs or “as a utility to unlock token-gated experiences.” As the website Decrypt wrote in a May 2021 profile of Leaving’s project, “Accessibility is still the biggest obstacle for crypto experiments like Genre DAO. Because the process of acquiring DAO tokens remains onerous and expensive, many DAOs are populated by the same small group of early adopters.”

I still don’t understand NFTs, but I understand why I’m not in a hurry to join in.

I'm glad to see that artists that have fewer options than I do are able to feed their families. But this seems less like a step toward a more egalitarian future, and more like a "how nice for you." Criticism13 of these opportunities may feel unnecessary, pessimistic, and harsh – we’re all just trying to eat! – but the forces of global capital are on the side of those seeking to legitimize cryptocurrency and acquire wealth. I think it’s good if trumpeting such hopelessly naive ideas as “art is not business” creates momentary discomfort for artists celebrating their successful cryptoart businesses.

As far as egalitarian futures, universal healthcare, debt cancellation, disarming police, access to clean water, and environmental justice would benefit millions of people in tangible ways that I can talk about without using words that didn’t exist a year ago. As with blockchain, I don't need a granular understanding of how universal healthcare works to know that it's wrong for people to die because they can't afford insulin.

I understand arguments that this technology is environmentally destructive and amplifies the commodification of traditional art markets. There's no question that cryptocurrency has been eagerly adopted by radical libertarians, profiteering real estate investors, Walmart, and other far right constituencies. Hope of achieving autonomy by acquiring wealth makes it easier to keep such company. Faith that such success will bring happiness makes it easier to believe that someone will solve these problems without compromising profit margins.

If you're willing and able to pass on opportunities to acquire money, power, and fame, some ethical dilemmas can be resolved more easily: When in doubt, opt-out. Or at least wait and see? After nearly three decades of writing about and making art, I still think art should be cheap and available to everybody. Regardless of whether or not there’s much hope of that actually happening.

Puzzling through this I kept coming back to the one weird trick the Zen Center’s guiding teacher shared with me for solving koans, the story-puzzles that are central to Zen training. Koans usually involve a paradox – what's the sound of one hand clapping, etc – and at their most obnoxious the answer involves a non-sequitur like putting a shoe on your head, or yelling about shit-covered sticks. My teacher's hint was also the first question I asked as a medic arriving on scene:

"How can I help?"

Daniel Chamberlin is an artist and writer living in Muncie, Indiana.

Thanks to Piotr Orlov, Jean-Hugues Kabuiku, Katherine Rae Mondo, Neil from Online, Karl Erickson, Whitney Joiner, and Rachel Buckmaster-Chamberlin for helping me understand why I don’t understand.

Thanks to Matthewdavid for making beautiful music and asking questions.

One of my favorite critiques came from an online friend who left it at “cryptocurrency sounds like money and money is bad.” Not surprisingly, there is much debate as to whether cryptocurrency is better understood as money, currency, or collective hallucination.

Cryptocurrency is also used for black market transactions ranging from the righteous to the abhorrent, but that’s easy to understand.

I found the work of David Gerard, Jacob Silverman, David Golumbia, and Jean-Hugues Kabuiku to be especially helpful.

One of the many revelations in the 2019 Hilma af Klimt documentary Beyond the Visible is that the lack of interest in this visionary artist’s catalog was due in part to the stipulation in her will that the work cannot be bought or sold. She was ignored and almost erased from history because investors couldn’t turn a profit.

This is a personal peeve and red flag: “Creative” is not synonymous with “artist.” Creative is the department at the advertising agency where artists and designers work.

On the pro-blockchain side of things, people suggested listening to Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s Interdependence podcast. This is a good example of the jargon and theory-heavy discourse between insiders that I find unconvincing. It’s not just that I don’t understand what they’re talking about, it’s that I don’t know if I understand it. Defending crypto seems to take a lot of work, and requires reading “energy use reports” and doing math. “Art is not business,” “life is more than debts and ledger entries,” or “Elon Musk likes crypto and you don’t even like meditation apps so you probably won’t like crypto” hits faster for me.

We should do this more often IMO. e.g. Debt is a virtue. Stop grinding. Naps are important.

Golumbia’s concise book is the best and most digestible explanation of cryptocurrency’s right wing politics that I’ve found outside of Twitter threads.

In addition to being Garfield’s home town, Muncie’s public television station is where Bob Ross got his start. The 2021 Bob Ross documentary Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed is yet another extremely depressing story about investors, fame, and other forms of success making people miserable and ruining beautiful things.

For those interested in destroying the State, the German anarchist Gustav Landauer had a similar idea in the early 20th Century when he wrote “the State is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of behavior; we destroy it be contracting other relationships, by behaving differently.”

[ahem] Like the eternal Tao, DAO isn’t something that anyone seems to be able to express in words . . . [rimshot] [audible groans, booing]

“There’s no ethical consumption under capitalism” means “please don’t yell at people who eat McDonald’s because they’re tired, it’s affordable, and their kids like it.” Not “if it doesn’t make dollars then it doesn’t make sense.”

sitting a few moments with this post. excellent, excellent. perhaps see also “intellectual dark matter”

I don't know. But I like the cat picture. 🐈💨

See: https://newmexnomad.blogspot.com/2023/03/multimedia-performances.html?m=1

for evidence of enthusiasm.