The Rent Is Always Too Damn High

Utopian housing dreams versus waking commune life in the Midwestern United States

This issue of our newsletter started out as they often do, where I sit down thinking “I’ll send a reminder of this week’s Inter-Dimensional Music broadcast, plus I’ll do a fast and loose write-up of stuff that I’ve enjoyed recently such as documentaries about Zen hermits, crusty psychedelic hardcore from Japan and Arizona, or that different kind of ramen I picked up at the international market in Indianapolis.” But then I start typing, crank up a mix of the aforementioned hardcore, stop drinking water, and voila! a couple thousand words of yelling about affordable housing and how artists – like me! and many of my friends! – aren’t any more special than anybody else when it comes to finding a place outta the rain.

Shout-out to our Taos affiliate for forwarding this New York Times story about Dreamtroit, “a Low-Cost Bohemia for Artists” that is apparently revving up in Motor City, and that I am just now realizing that I have been erroneously referring to as Detroitopia.

I like Detroit. I like to think about new ways to support the sort of communities that support my mental health. And I like to hear ideas about how we can make the essential daily tasks of finding food, shelter, and medicine a little bit easier for everyone. So this recent story about a low-cost artist community in Detroit is relevant to my interests. That being said . . . I’ve worked on fundraising for similar-sounding projects and it burned me out on nonprofit development work probably forever. Raising money for allegedly affordable housing specifically targeted at artists – which, to me, is problematic from jump – left me with a bad taste in my mouth for a lot of reasons. That familiar bad taste started to come back reading about Dreamtroit – a project “in the vanguard of new development poised to transform moribund automotive facilities into affordable housing” – and quickly encountering a protagonist described as a “financially savvy realist.”

But the first real red flag – and not the good kind of red flag to a cranky middle-aged anarcho-communist cosplayer such as myself – started flapping in the wind when the author equates “entrepreneurial spirit” with DIY culture, which sorta feels like when people confuse mutual aid and charity. One is a radically different way of living that fosters solidarity and autonomy, and the other is a gentler form of the same old exploitation, given a fresh veneer mostly due to the increasingly dire state of affairs for anyone who isn’t already growing rich from the current capitalist operating system.

My emergent frustration with this nice article about a likely well-intentioned real estate development hinged on what the story meant by “affordable” and “housing.” If your monthly rent payments are lower, staying alive – and making art that isn’t intended primarily as an exclusive commodity – gets a lot easier real fast. Skim over the inspirational soundbites from Dreamtroit investors and residents though, and it turns out a 1,000 square-foot two-bedroom apartment at Dreamtroit goes for $2,000/month. Meanwhile, the median gross rent in waking Detroit is $1,040 according to US Census1 data.

The $2,000/month price tag also places 2BR Dreamtroit apartments in the top 4% of “occupied units paying rent Detroit city, Michigan.” Maybe I misunderstand, after all I am an artist who makes negative money from art, and subsists almost entirely through a practice of radical dependence on my like-minded partner who also happens to have a resume that is better suited for finding jobs that provide health insurance. Not super good at budgets, me. But this is not very complicated math, and the data shows up on the first page of search results for anyone who doesn’t accept a real estate development’s publicity materials without question.

Dreamtroit’s $2,000 security deposit on a 2BR unit brings the rent to $26,000 for the first year. Those with an interspecies household should probably expect to add the ubiquitous grift of “pet rent” which I assume is what they mean by “pets negotiable.” Weirdly enough, this data point is followed by the line “More than half the units are reserved for artists making $33,500 to $40,000 a year.” I’m guessing those units are the less lucrative “communal space with shared kitchens and bathrooms” for $365/month. The cheapest unit available at the time of this writing in October 2024 is a 400-square-foot studio for $950/month plus $50 application fee and $950 security deposit.

“[Dreamtroit] is not exactly family friendly,” is the only slightly skeptical observation in this glowing article. “To economize, kitchen cabinets and bathroom doors do not have hardware — just holes for residents to open them with fingers.” I wonder how much money they saved by skimping on cabinet handles, at the price of excluding families, as well as anyone who prefers or perhaps even requires an extremely normal level of accessibility hardware such as a handle on the communal toilet door. As someone who has lived in houses with communal toilets, I can say that handles are pretty important.

If we’re relying on advice from random financial websites and we go with the “spend no more than 30% of your income on rent” guideline, that means an “affordable” 2BR Detroitopia apartment is out of reach for artists bringing in less than $87,000/year. This may be alluring to people priced out of Los Angeles, Brooklyn, Austin, Chicago, or Portland. But this is Detroit, where the median household income is $38,080/year. For that matter, the median household income for the entire Midwest region of the United States is around $70k depending on which source you’re looking at.

$70k is significantly more than I make from hosting $10 Basking in Gravity psychedelic death yoga sessions where no one is turned away for lack of funds. Most of the artists that I know bring in much less than $87k, though to be fair my cohort is different than the class of artists in the NYT story, which includes a graffiti guy who “has clients that include the Detroit Lions” and a globe-trotting sculptor and former Burning Man employee with his own Wikipedia page.

The line “the vibe is that of a commune . . .” is the thing that really grinds my gears though. Communes are real things that can offer a glimpse of a different way of living, not just the whiff of a chill vibe that comes from hanging out with your hip neighbors.

Last summer when I was doing the Basking in Gravity tour I had a couple of conversations about housing while crashing with several friends who I consider to be artists. Although “art” isn’t necessarily how they pay for food and shelter. Are massage therapists doing amateur wildlife photography creative enough to be eligible for Dreamtroit? Are writers, broadcasters, or musicians considered artists? Can living a life based on principles of radical acceptance be considered a creative practice?

One of those friends lives in a private bedroom in a co-op in Berkeley, the other occupies a cozy one bedroom apartment in a Portland, Oregon ecovillage. While both of these setups have considerable benefits2 like lower rent, high community engagement, and a dozen different types of compost piles, neither of them are communes. For comparison, I used my experience living for a couple years at the Indianapolis Zen Center, which I think probably qualifies as a commune, or at least it’s part of the Kwan Um School of Zen, a religious nonprofit. I paid $400/month for my own room with enough space for a bed, a reading chair, and a minimal Inter-Dimensional Music home studio. There was also a bathroom shared with one other person, that featured the smallest and most uncomfortable shower I’ve ever used. Plus as many meditation retreats as I could sit.

The biggest difference between these three housing arrangements was obviously gonna be financial. While each of my friends’ rent was higher than mine, it was still comparable in the context of both prohibitively expensive cities. However, at the Zen Center, there was no lease, only a verbal commitment to following a broad set of basic Buddhist rules: no guns, no meat, no booze. Although the septuagenarian guiding teacher had declared the garage a “dharma-free zone,” and while he kept with the prohibition on firearms, he had stashed hot dogs and home-brewed peach schnapps there. We were also each expected to make dinner once a week, which was a low pressure proposition. E.g. a first-time vegetarian chef felt fine boiling some noodles til they fell apart, dropping a brick of raw tofu into a pot of canned marinara sauce, and calling it a meal. This was a religious community, not a rooming house, so residents were expected to attend meditation – including three weekday 6:30am sessions – as often as possible.

This meant that when I quit my job at an arts nonprofit because – among many other reasons – I was uncomfortable with their artist housing project, I told the same guiding teacher with the cache of cased meat and fruit hooch that I wasn’t going to pay rent for awhile. I wasn’t a jerk about it, and I also put in a decent amount of time cleaning our house, publishing the IZC newsletter, running social media, and building a new website. He wasn’t exactly pleased with this development. He also didn’t kick me out. I knew that living rent-free wasn’t gonna be forever – these were Buddhists, not squat-or-rot anarchists despite a common enthusiasm for dumpster-diving – but he and I kept talking about the situation, and it lasted a couple months without conflict. After I moved in with my girlfriend Rachel in Muncie, there was no back rent to pay, and nothing but love when we returned to get married in the dharma room a few months later.

“To live in a [Zen Center] community is not easy,” Zen Master Wu Bong, a teacher in the Kwan Um School says in “The Practice of Together Action and Buddhist Wisdom,” a 2008 dharma talk. He continues:

There is a structure and a set of rules that must be followed. There is less privacy than one would have living outside such a community. There are people living in the community or visiting it with whom one would have nothing to do if given the choice. There is sometimes food one does not like, and often a lack of food that one likes. There is the “getting up in the morning,” one of the greatest problems facing a Center resident.

There are, of course, pluses to being a resident. There is a structure and a set of rules that help us put down our checking mind and help our discipline. With less privacy, there is more openness and less need to hide behind one’s image. There are people with whom one learns to deal correctly, notwithstanding feelings of like or dislike. There is the opportunity to learn to appreciate food, and not be hindered by its taste. There is the joy and energy of getting up in the morning and practicing with the rest of the community.

To be a resident in a Zen community . . . is to let go completely of one’s opinions. This is something which is impossible to do without the practice of “together action.” Only by acting together with others do we discover the boundaries set up by our habits, our prejudices, our likes and dislikes - in other words, our karma. Only by experiencing our boundaries can we let go. Only by letting go can we allow our natural wisdom to grow.

Like I said earlier, a commune is a real thing that is beautiful and funny and difficult and sometimes gross and super annoying. It’s not just a mellow hang-out vibe. The most profound thing I learned from two years living at a Zen Center was how to not be a shit head when it’s my turn to do the dishes. And that my place in the community doesn’t depend on my ability to come up with rent.

The problem of houseless-ness isn’t a lack of housing for the tiny percentage of ambitious, entrepreneurial artists who are somehow making more than the median income for the region where they live. It’s also not caused by the nonsensical and deeply racist assertion from Republicans that affordable housing has been gobbled up by hordes of non-white migrants. The problem is that housing shouldn’t be a commodity. Or at least there should be non-commodity options for people who need to secure this basic human right in order to stay alive. People shouldn’t be trying to profit from humans’ need for shelter, or medical care, or their need to acquire baseline survival requirements from tampons to nutritious food.

And by “people who need housing” I mean people, not an elevated class of people who call themselves artists. I’m an artist, I’m friends with lots of artists, and sorry to be a downer guys but we aren’t special just because we make things and spout esoteric rhetoric about what they’re supposed to mean. People need a place out of the weather more than they need big freaky sculptures, beautiful paintings, or affordable psychedelic death yoga experiences.

This last winter Rachel and I answered an emergency call from the Muncie Folk Collective, when the City of Muncie decided to shut down The Muncie Inn – our local “meth motel” – with two weeks notice during January’s sub-freezing temperatures. And by “meth motel” I mean one of the only options for residents – methamphetamine addiction notwithstanding – who can afford weekly rent, but can’t scratch together a thousand bucks to pay for whatever combination of first and last month’s rent and security deposit is required by the local student housing slumlords. The Muncie Inn’s one room accommodations had nowhere to cook, intermittent heating, and infestations of roaches and bed bugs. At $250/week, these rooms were only slightly cheaper than what we pay for our very stylish and comfortable two-bedroom apartment with new appliances, 10-foot ceilings, original hardwood floors, and views of Muncie’s brutalist architecture skyline. The only difference is that my partner has a normal job with a modest Midwestern salary at a public university, and we have the ability to come up with a couple thousand bucks. Even if it means putting groceries on a credit card if we run low on eggs or exotic instant ramen too close to payday.

Muncie street outreach activists negotiated with the aforementioned slumlords to try and set up weekly rent situations in the crumbling old houses aggressively subdivided into apartments in the student ghettoes surrounding Ball State. Lots of people answered the call for donations of household goods – Muncie Folk Collective and others stockpiled everything from new microwaves to razors, winter coats, and surplus-size cans of soup in a makeshift distribution center downtown – but there were only a half dozen of us that showed up to help our neighbors with the actual move. Which was hard enough without having to witness entire families vacating single room apartments, pregnant women moved to tears because someone set aside a set of fancy skin cream for them in addition to diapers, or down-on-their-luck fur mamas making Sophie’s Choices over which of their pets they have to abandon in order to comply with their new leases.

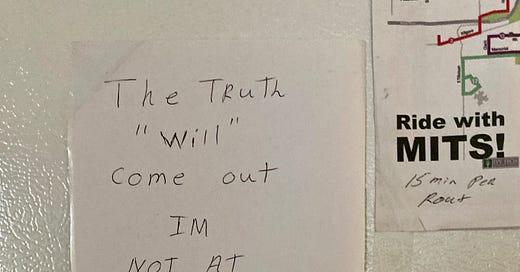

A few months later I got the call again when some of the same people started getting evicted from their new homes once landlords rescinded the weekly-rent option. This time the process was faster, both because most folks had pared down their already meager belongings in the first move, and also because we had to get them out before the sheriffs arrived to forcibly remove them from their homes. As a hand-written note that one of the residents left stuck to the wall of their crummy former apartment reads, “You made your mind up before you didn’t offer me a payment plan or put [me] on one. [You] refused my offer. $176 x 4 = $700.”

To be fair, Dreamtroit seems like a cool place to live with cool people who are working on cool art projects. The apartments look nice. At best it’s an ambitious urban beautification project, a welcome rehabilitation of an abandoned industrial site. And at worst it seems like a not-wildly-overpriced apartment complex in a hip neighborhood, marketed to upwardly mobile, financially successful professional artists. Which is hardly a nefarious undertaking. But that’s probably not enough to get a story in the New York Times.

Naimi and Goldenberg’s commitment to a low-cost bohemia for artists arrived at a pivotal moment. The complex sits at the edge of a $3 billion mega-development by Henry Ford Health, to include a new hospital tower, medical research center and housing and retail development. The latter project is led by Tom Gores, founder of Platinum Equity, a private equity firm and owner of the Detroit Pistons basketball team. A neighbor, the Motown Museum, has been planning its own major expansion.

Given the billion-dollar juggernaut in their midst, Cox, the informal adviser, said Dreamtroit “is a point of resistance against institutional development.”

The Dreamtroit real estate development only looks like a “point of resistance” in comparison to that billion-dollar juggernaut, or when held up against any other city’s explicitly commercial developments. It can only maintain a facade of affordability for readers struggling to live in coastal metropolises in a time of rapidly increasing wealth inequality worldwide. Like all rental properties, Dreamtroit is a wealth redistribution scheme where moneyed investors and developers acquire passive income from people who can’t afford to purchase property for themselves. Even extremely successful artists like those in the NYT profile usually lack job security, and have to deal with wildly unstable income flows. There is no mention of contingencies for helping the graffiti artist keep his home when his NFL client is late with a payment, or when a curator suddenly changes their mind about an exhibition. If any of these artists’ creative practices fail to remain profitable, they have acquired no capital, there is no return on their investment. They’re out on their ass like anyone else, rejoining the masses of non-artist philistines looking for housing options that are actually affordable assuming the sort of modest income they might hope to get from a job that offers the luxury of a schedule where they can keep making art.

As D Land Group, the property management firm that handles Dreamtroit, makes clear through their website’s owner portal, “we serve as investment consultants.” Their self-described priority is keeping owners “connected to your property.” That means this a cool apartment with a “post-industrial” aesthetic and wacky neighbors, but not much else. While the article makes space to mention that one of Dreamtroit’s kooky founders “proudly wears a hard hat with his nickname, UNCLE MEATBALL” – can you imagine! – there isn’t any discussion of the D Land Group president’s background in industrial supply distribution, private equity, and “disruptive distribution technology.” Nor is there further clarification of how offering renovated apartments to artists at twice Detroit’s median rent constitutes a “point of resistance.”

While this puff piece on an aesthetically pleasing apartment complex isn’t surprising, there’s a depressing effect that arises from such a casual lowering of expectations. If I’m an artist who would benefit from affordable housing, but my partner and I can’t imagine being able to afford a place in this affordable artist community, am I a failure? How naive am I to pick up an article like this thinking it might suggest an alternative living arrangement where we might be able to worry less about making rent each month? What’s the value of a community where you’re banished if you can’t offer up 30% of your income in monthly installments? Is this the limit of what is possible? When anarchist activist and anthropologist David Graeber typed out the oft-quoted line “the ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently” I believe he’s suggesting something more than enabling artists to make a $2,000/month payment to wealthy real estate investors for a decent apartment that lacks bathroom door handles.

I believe that artists – like me! and my friends! – deserve affordable housing. On the same trip West last summer, I saw a clumsy analogue with weed legalization in the Bay Area: Maybe we should’ve focused on exoneration and reparations for the savvy ahead-of-the-curve cannabis entrepreneurs who are still imprisoned, rather that prioritizing easy access to weaponized marijuana strains for the tech bro swerving down Haight Street in his Tesla, doing dabs and yelling stoned slurs at crusty change-seeking skaters.

Maybe we should prioritize affordable housing for artists who make things that don’t provide an $87,000 year annual income, or people breaking their backs for $15/hour at an Amazon warehouse, or people who don’t have any money and struggle with addiction but still deserve to not die of hypothermia – before worrying about whether or not former Burning Man employees can pay for a 6,000-square-foot studio at Dreamtroit. Or at least that’s my position until I figure out how to get the NFL to add my psychedelic death yoga experience to the Indianapolis Colts’ training camp schedule.

If you know anyone who might enjoy Vøid Contemplation Tactics or Basking in Gravity, please pass it along. It means a lot! Thank you.

Word of mouth is our primary form of promotion. Vøid Contemplation Tactics doesn’t do much on social media, which is good for our mental health. As Dōgen's teacher told him, “You don't have to collect many people like clouds. Sitting with many fake practitioners is inferior to sitting with a few genuine practitioners. Choose a small number of true persons of the way and become friends with them.”

Thank you for lurking anonymously, subscribing for free, or subscribing for money. If you’d like to support these projects with a one-time donation, you can also drop some change in the tip jar.

Most of this census data comes from https://data.census.gov/profile/Detroit_city,_Michigan?g=160XX00US2622000

Also my friend’s neighbor at the ecovillage is the original singer for Nausea so I was very impressed.

Thinking yet again about the apartments I shared with friends where our cut was somewhere between $233-350 a month, the janky-but-safe-roof-over-my-head $300/month duplex that a pastor friend (whose family now has their own housing struggles in Berlin working with Syrian refugees who have even harder housing struggles) rented to me when my living situation in my mid-20s became abusive. I never paid more than $600 a month in rent in Cleveland until I bought a house when I saw the rents everywhere double as private equity scooped up everything and people here got greedy. The rust belt was great for this once if you had a halfway decent job /good roommates. It's not anymore, and I think a lot about how all this "creative class" stuff ends up being trickle-down economics for the NPR crowd, I always remembered Detroit being cheaper and then I was horrified the last time I snooped around Zillow up there.

I witnessed and was approximate to so much of the same weird shit in Vancouver, where people discuss housing like Texans talk about weather. I’m very wary of any subsidized housing project geared towards artists—so many icky complications