There's Always This Moment II

Midwest myths, G N' R Lies, and a few ignoble basketball truths

This is the second part of an essay about basketball, Zen, reggae, hairstyles, and sundown towns, among several other things. It will make more sense after you read the first one, which you can find here:

The Indianpolis Zen Center, Red Key Tavern, and All in The Wrists barber shop didn’t make me a Pacers fan, but these communities gave me reasons to feel good about returning to Indiana in 2016, after 20 years in Southern California and Far West Texas. I was never proud of being from Indiana because I was from Zionsville, a deeply racist and conservative Indianapolis suburb, where I went from the first day of kindergarten to high school graduation with a cohort that was almost entirely white, and 0% Black. A couple of lifelong friends are from Zionsville, and my childhood was pretty idyllic, but pride in being from Zionsville was White Pride by default. And despite driving to Indianapolis for punk rock shows in high school, followed by three years of undergrad at Indiana University in Bloomington, my home town remained the default image of Indiana. The racism in Zionsville was thoroughly modern and “polite,” and it looks like I everything I hate about the right wing and their spineless liberal enablers.

“In the normal course of human events,” sociologist James W. Loewen writes in his history of sundown towns like Zionsville, “most and perhaps all towns would not be all white. Racial exclusion was required.” He goes on to quote from Tim Wise’s White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son: “If people of color aren’t around, there’s a reason.”

I have few recollections of Zionsville’s high school basketball team. Football and basketball players all looked alike to me. There were no braids, dreads, or fades, just buzz cut jocks, sworn enemies who had been inflicting humiliating violence on nerds like me since my first days at school. As far as the NBA went, I didn’t care about anyone other than the Lakers because I thought Kareem Abdul Jabbar was one of the coolest humans I’d ever laid eyes on: I was more curious about his protective goggles, dashikis, and boycott of the Olympics than his playing style. Meanwhile Larry Bird was a dead ringer for the shit head kid with a lip full of dip who hit me in the back of the head every morning on the bus ride to school.

Growing up, I shot many lonely baskets with Peaceful Brown – my only neighbor, a now RIP pal (the nickname came from his surname, not his skin color) who once told me without malice that I should try football instead of basketball “because you’re fat” – on our gravel driveway out in the cornfields. Along with our house’s lack of a basement or a second-story, and our rural route address far beyond the cable company’s range of service, the gravel drive was something that I perceived as a mark of “poverty,” mostly because it was hard to dribble on crushed stone, and impossible to skate over. My friends in subdivision McMansions watched MTV in basement home theaters, and practiced ollies and crossover dribbling on freshly paved cul-de-sacs.

Other than that, my only significant experience playing basketball in high school happened at the end of gym class. Partly out of a need to defend myself against shitty bullies, and partly because they were cool and knew about music, I was a nerd seeking refuge with the school’s punk rock skater clique. We either outright refused to participate in the official physical fitness syllabus, or opted-out with performatively lackluster efforts. Upon returning from the locker room in our street clothes, we’d tear up the courts until the bell rang, working up a sweat and annoying the gym teachers by playing an extremely chaotic and aggressive form of basketball.

We threw the rock at each other like a dodgeball, tackled the ball handler and pinned them to the floor, and ignored rules and fouls and keeping score. It was basketball-as-mosh pit, a proto-Jackass junior varsity melee, sporting violence by teenagers in Vision Street Wear and Slayer T-shirts who knew more about circle pits and stage diving than pick-and-rolling. It felt like physical liberation to me as a person who wasn’t good at sports and hated my body. I was getting attention for rowdy masculine prowess, wearing bruises and skinned knees with pride. I ended up missing out on the freshman year roller-skating party after getting hit in the head by a flying basketball, spending the afternoon with an osteopath manipulating the rib I’d popped out of place instead.

In a school where almost everyone was white, I had long counted myself among the downpressed because I was not cool and we were not wealthy. The punks and the skaters got plenty of abuse too, but they weren’t meek in their response. Many years later, living in Los Angeles and writing about rap music, I would refamiliarize myself with basketball as one of the extra credit pillars of hip-hop. But in Zionsville we had to play a different game. Basketball was still the provenance of white jock overseers.

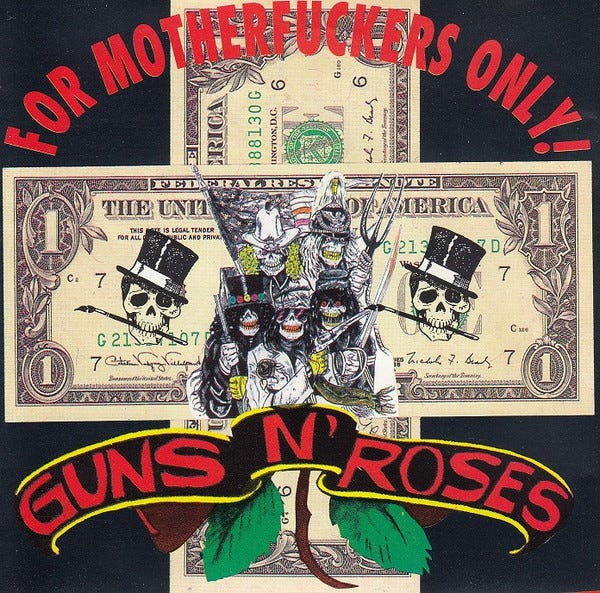

The stain on this memory is not unlike the stain “One In A Million” leaves on the already somewhat problematic discography of fellow Hoosier Axl Rose and his popular band Guns N’ Roses. Some of my skater kindred referred to our pickup games of berserker ball with an adjective form of the hard R n-bomb that Axl deploys in the opening verse of the last song on their underwhelming 1988 sophomore album G N' R Lies.

I already knew that using slurs was wrong. I was a member of a Christian Nationalist church, not a White Nationalist church: There was only one Black family of four in our congregation, but that was more Black people than in my high school. I was relieved when someone suggested “street ball” as a slightly less explicitly racist name for our rambunctious activity.

At this point in my youth I’d heard the N-word more often from white people than Black people. But not how you might think. I’m talking about songs by the Dead Kennedys, Jane’s Addiction, Seven Seconds, Patti Smith, X, and JG “Foetus” Thirlwell. The N-word with the soft A was bleeped out of rap videos on low-rent broadcast television MTV knock-off The Box, as well as the occasional hip-hop single on local R&B station WTLC, but not on my dubbed cassette copy of Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death.

I understood that these white musicians’ use of the slur was not equivalent to the racist jokes I might hear at school. But it wouldn’t be until I was earning an increasingly worthless degree in comparative literature at Indiana University that I would learn terms like “complicitous critique.” I just knew the vibe was wrong. If my parents were home, I’d scramble to turn the volume down for that one verse on “Holiday in Cambodia” just as fast as I would for the “Last Caress” lyrics about murdering babies and sexually assaulting your mom. As further example of the naïveté that can arise from a racially and culturally monochromatic childhood in a staunchly right wing community, before giving a proper listen to N.W.A. I assumed that Efil4zaggin meant Ren, Dre, and Eazy were “pro-life” anti-choice activists, which was a positive for me at the time given my church affiliation. I thought maybe N.W.A. was like rap’s U2 or something.

The skater buds who casually dropped the slur as a descriptor for the type of basketball we played probably would’ve used a defense similar to Axl’s dumb bullshit:

“I don’t like being told what I can and what I can’t say. The word n****r doesn’t necessarily mean black. Doesn’t John Lennon have a song ‘Woman Is the N****r of the World’? There’s a rap group, N.W.A., N*****s With Attitude. I mean, they’re proud of that word. More power to them.”

Crying about not being able to say the N-word usually involves the complainant saying the N-word, because anyone can say the N-word. As is often the case in these exchanges, Axl is complaining about the consequences of saying the N-word. It’s easier to avoid those consequences when there aren’t any Black people around. While this quote doesn’t do Axl any favors, at least he doesn’t immediately go to the “but my friend Slash is Black” defense. In other interviews at the time, Axl’s Black friend doesn’t sound too stoked about this anyway.

It’s easier to consider Jello Biafra or Patti Smith as satirists than it is to perceive Axl’s lyrics as the voice of a character, ugly social critique rather than uncut racism. Perhaps because Axl’s artistically-licensed racism seemed more authentic the more he struggled and failed to defend himself, or maybe due to the significant number of the band’s intentionally and actively racist fans. But while X singer and fellow N-word sayer Exene Cervenka gradually morphed into an Info Wars-pilled Sandy Hook denier partial to Confederate flag pins, by 1992 Axl was already proto-woke, telling Interview Magazine,

“l don’t perform [‘One in a Million’] because l think it’s too dangerous and l don’t trust people with the song. I don’t trust the audience with the song. I don’t want to do ‘One in a Million’ on stage and know that there’s a lot of people out there in the crowd who are prejudiced and it’s gonna help fuel their fire. l don’t like the damage that that song does.”

In the time since, the list of white artists using artistic license to drop an N-bomb has grown to include John Mayer in a very uncomfortably horned-up Playboy interview, and the extremely rude sludge metal band Eyehategod. Surprisingly late to the party, Green Day dropped a satirical hard-R N-bomb on 2004’s American Idiot. The same year the gratingly twee cringe-folk duo CocoRosie deployed the slur twice in the chorus to “Jesus Loves Me,” a song delivered in a vocal style that could easily be heard as Billie Holiday blackface. As we discussed earlier regarding white people attempting to use the correct pronunciation of Rastafarian terminology, you’re probably fine as long as you don’t do the voice.

Other than Mayer’s apologies on Twitter, as far as I know it’s only Guns N’ Fuckin’ Roses and Eyehategod that took action after listening to their critics. In a rare instance of band cohesiveness, Axl & Company unanimously chose to pull “On In A Million” from reissues, and while Eyehategod is still too chummy with racist dipshit jock-jammer Phil Anselmo for my taste, their setlist now includes a song rebooted as “White Neighbor.” Neither Axl nor I like being told what to do, but unfortunately Axl stuck to those famous guns when his Black friends surely cautioned him against cornrows, just as mine steered me clear of dreadlocks.

This isn’t a defense of casual racism in Central Indiana. These are examples of why I’m not proud of where I’m from. But that doesn’t change the way I grew up. When I was in elementary school, I thought we were poor and I was fat because my dad wasn’t a doctor or lawyer and I wore husky Rustler jeans from Kmart. By high school I was paying for my own Levi’s from JC Penney, but I still thought I was fat and I didn’t want people to know I was from Zionsville because they’d think I was a spoiled, racist rich kid as well. I didn’t spend much time with Black people until college, but I went deep enough into hip-hop and reggae and Bad Brains by my sophomore year of high school that I sometimes wore a red, gold, and green Africa medallion dangling over my Joy Division shirt, blissfully unaware of yet another paradoxical juxtaposition of ideologies. Oddly enough, years later this very same culture clash would serve as the organizing principle behind Jäh Division, my favorite side project of the noisy psych rock band Oneida.

While I embraced the harsh hxc ethical code of straight edge as safe passage out of Christianity – an easy pivot from youth group to youth crew – I was quietly wary of the hardline rules laid down by Minor Threat. I wasn’t so sure about the band’s “Guilty of Being White” song either, but latter day Dischord mainstays Fugazi and Lungfish both offered passage into the world of dub and jazz, Ian MacKaye’s evolving contributions to the culture counterbalancing poor decisions made in those salad days.

Likewise, going to reggae shows in high school helped keep the boring puritanical aspects of youth crew politics in check. Whirling awkwardly in sweaty circle pits at the Broad Ripple Community Center offered more opportunities for physical catharsis and made it easier to endure the harsh clatter of Indianapolis hardcore bands, but I was too square to join in the easy-skanking on Sunday afternoons at Broad Ripple Park. Instead nodding my head out of time in the back of the crowd with a friend in matching Doc Martens, him with a dyed-blond devil lock and me in a Sisters of Mercy T-shirt and baggy shorts. I also noticed that the hand-rolled cigarettes at punky reggae parties smelled nicer than the ones at parties that were just punky.

As with many places in the North, there’s a history of racism in Muncie – the East Central Indiana city where I live now – that is too easily glossed over with a liberal veneer. You’ll still see a handful of Confederate flags flying in certain neighborhoods. One morning I walked past a black truck with a 14-881 decal parked at the Delaware County Emergency Management Center. And the former headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan is just down the street from our apartment – though not long ago it was renovated by a local performance artist into a queer-forward dance studio with full-spectrum Pride and BLM flags flapping out front. Muncie had a couple sundown neighborhoods at the beginning of the 20th Century, but by the 2000 census the city of almost 70,000 people was 13% African-American, with a median household income of $26,613. As of 2020, Zionsville was still 91.4% White, 1.4% African American, with a median household income of $137k.

There’s still racism in Indiana, but it’s more insidious than the unhoused bicycle mechanic I met with the stars ‘n’ bars tattooed on his arm. The current Indiana governor – Republican Mike Braun – came to national attention for suggesting that the legality of interracial marriage should be left to the states, and then got elected in a landslide. Then in April 2025, Braun’s lieutenant governor, Republican Micah Beckwith, posted a video on twitter defending the Three-Fifths Compromise, an agreement from the 1787 Constitutional Convention that counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person, giving the slavery-based economies of the south more political power and lower taxes. The last “good” Republican governor, Mitch Daniels, pressured Indiana colleges to cancel a book tour by the author of Sundown Towns because he thought it would scare businesses away from the state.

But my experience in Zionsville sounds alien to my wife Rachel. She grew up in Muncie with lots of Black friends and classmates. In addition to punk rock and hip-hop shows, she also went to more basketball games as the statistician for her high school team. This is in part because Zionsville and suburbs like it are still operating with the camouflaged form of middle-class neoliberal racism that aggressively resists the label of racism. Unemployed Sons of the Confederacy with unfortunate peckerwood tattoos are easier to spot and a lot less powerful than the smiling pant-suited Republican mayor of the posh Indianapolis suburb Carmel, a woman whose electoral victory was marked by the eye-catching AP headline “Candidate who wouldn’t denounce Moms for Liberty chapter after Hitler quote wins Indiana mayor race.”

Learning to appreciate basketball, and watching the Pacers journey to their first NBA Finals series since 2000, has given me a reason to be happy for Indiana, but that’s not the same thing as being proud. Despite the best efforts of right wing government officials to undo any legislation making life easier for everyday people, and despite an electoral map gerrymandered by those same Republicans into a white supremacist jigsaw puzzle, I can see an Indiana that is something more, something better than ‘80s Zionsville, or the ‘25 state government. But I left the Midwest after college. Other than helping the Indianapolis Zen Center become more inclusive – I learned a lot about what “inclusion” feels like at my appointments at All In The Wrists, and could better understand what it might feel like for a person who is not a mildly depressed white man with a close-cropped haircut to visit a dharma room full of mildly depressed white men with close-cropped haircuts – I didn’t contribute much to the things that I like about Indiana.

So in the run-up to the playoffs, I was confused and eventually kinda angry over how often people shitted on the Pacers. As the team slowly battled their way up the Eastern Conference rankings, I began to detect the subtle shade when their many victories were attributed to injured opponents or negligent referees. Prior to nearly sweeping the top-ranked Cleveland Cavaliers in the playoffs, and once again defeating the highly favored Knicks, Pacers point guard Tyrese Haliburton was ranked by his NBA comrades as the most overrated player in the league. As more and more commentators have started to admit, at some point you gotta stop referring to every win by one of the most dynamic, top-ranking teams in basketball as an “upset.”

Pacers hate is so pervasive that it even leaked into my usual housecleaning soundtrack of left wing comedy podcasts. “I have disliked the Indiana Pacers for longer than any other pro sports franchise,” David J. Roth declared in an aside at the end of a recent Chapo Trap House episode. “I’m rooting for a Knicks-Timberwolves finals.”

I am a clueless neophyte, while Roth is a professional sports writer and political critic whose writing about the day-to-day lived experience under American fascism is some of my favorite contemporary commentary. The Pacers and Knicks are longtime rivals, though Haliburton squaring off with Knicks point guard Jalen Brunson at pro wrestling matches suggests this is not much of a blood feud. So Roth is rooting against two underdogs from wildly enthusiastic secondary market teams – the Oklahoma City Thunder and the Pacers are the youngest, most collaborative, fastest, goofiest, and downright weirdest teams in the NBA. They’re both good in large part because the team owners have kept these men together for years, rather than subjecting the players that they “own” to cynical trades. And the Pacers are not just dude’s least favorite basketball franchise, but his most disliked team in all of professional sports? It’s probably easier to say things like this if there aren’t any people from Indiana around.

And now suddenly I am in way over my head, not just talking about basketball, but talking shit about sports writers that I like, rather than talking about not talking about basketball.

Watching Pacers games in Indiana is not easy, because the NBA is just as mired in a tangle of profit-maximizing capitalist schemes as every other social and cultural institution. Outside of a few months in 2001, I’ve never paid for a cable subscription. Growing up, we lived too far from town to be eligible for cable, which my conservative parents wouldn’t have signed up for anyway. When the FCC made the switch from analog to digital TV broadcasting, I lived in Marfa, Texas, hundreds of miles beyond the broadcast range of network affiliates in El Paso or Midland/Odessa.

When I moved from the Indy Zen Center to a Muncie apartment and stopped visiting the Red Key, the digital antenna I used for the first time only caught one channel, the local PBS affiliate. I had no idea how to watch basketball for free that didn’t involve black market streaming websites that required a half hour of dodging and weaving between gnarly sex game pop-ups and malware downloads disguised as “play” buttons in order to access a glitchy Brazilian stream guaranteed to stutter and cut out at every dunk or three-point attempt.

An NBA League Pass subscription solved some of these problems. I ignored that option for too long, mostly because I thought it would be as prohibitively expensive and confusing as the NFL streaming service. But basketball is different from football in many ways. There are a lot more games in basketball. While the NFL was voluntarily licking boots and scrubbing the milquetoast “End Racism” text from end zones after Trump’s election in 2024, NBA games were bookended by graphics celebrating HBCU month, without even bothering to expand the acronym. It’s also nice to watch tremendous feats of athletic prowess without all the slow-motion traumatic brain injury footage.

As with art, music, and bougie Zen seminars, the price of accessing a sports experience tells you a lot about who the experience is for. Unlike the NFL, in-person Pacers games – especially regular season matchups here in Indiana – are for whole families, who can have a night out in the nosebleeds without committing to a Capital One indentured servitude program. The same was true with League Pass: We signed up for an introductory subscription with a “dot edu” email address education discount and gained access to hundreds of games for $9 a month.

In an era where streaming services are becoming less functional and more riddled with ads and algorithmically-driven auto-start selections, League Pass was a revelation. If you don’t watch the games live – and as a non-denominational fan I didn’t care about spoilers and rarely encountered sports commentary on my timeline2 anyway – the ads are replaced by “in-arena entertainment,” which includes Drip Cams set to a loop of OT Genasis’ raunchy “I Look Good” earworm, bonkers jump-rope stunts, an acrobatic woman in a reflective leotard target shooting a compound bow with her feet, and “the skateboarding fiddler.” One OKC game featured a free-throw contest where the prize was a year’s supply of sliced white sandwich bread. With League Pass’ slow-motion effect you can slow down everything and make the national anthem singer sound drunk and off-key, in addition to choose-your-own-replays of obvious things like dunks or foot archery.

It’s the basketball equivalent of “matrix”-style Grateful Dead bootlegs, delicate patchworks of audience recordings and soundboard tapes, where the band comes through clearly in harmony with the crowd, a reminder that these happenings don’t take place in a vacuum, but are living, breathing ecosystems. Myles Turner’s thoughts about in-person yoga are relevant playing basketball, attending games, or watching on TV: “It’s so much better not doing it on your own.”

While NBA games appeared and disappeared on TNT and HBO and ABC and ESPN as the result of confusing licensing deals, at worst they ended up on League Pass three hours after the buzzer: not a big deal if you, like me, were just looking to “watch basketball,” often with the sound down and headphones playing podcasts or ambient jams. But a problem came to my attention when Rachel – a dedicated Pacers fan – got involved: Pacers games are blacked out locally on League Pass, regardless of whether they’ve sold out at the arena. And they don’t show up on League Pass until 72 hours later, a blatantly punitive delay which means she’s already seen spoilers and I’ve found another game to watch.

If you want to watch Pacers games in Indiana – and as basketball gossip online quickly reveals, few people want to watch Pacers games outside of Indiana – you have to sign up for a cable package of some kind, but that’s not enough. Figuring out How to Watch Every NBA Basketball Game on a Streaming Service was already so complicated in 2023 that Wired gave up on explaining it in the SEO-optimized explainer “How to Watch Every NBA Basketball Game on a Streaming Service”:

Nationally televised games are played on four networks: ABC, ESPN (for which ESPN2 acts as a secondary station), TNT (for which TBS acts as a secondary station), and NBA TV. But unlike with NFL games, not all NBA games air on national networks. Many games air only on regional sports channels, such as Bally Sports and AT&T's SportsNet. All of them strike coverage agreements that vary from team to team, region to region, and game to game so widely that it's impossible to cover them all in this guide.

Many Pacers games are only available in Indiana by adding the Fanduel Network to an already pricey cable subscription, turning your living room into a seedy OTB. Which means it’s now $100 or more each month to access games that were previously available for free to anyone with a TV antenna. It sucks if you can’t watch Utah Jazz games in Maine, but it’s cruel when this profiteering means you can’t watch Indiana Pacers games in Indiana.

And then there’s the whole repellent gambling thing. It’s not just that there are advertisements for the online gambling services that ruin peoples’ lives during every commercial break, but the gambling companies literally own the network that broadcasts the games. It’s gross to see powerful sports legends and beloved commentators like Shaq – whose net worth is estimated to be around $500 million dollars – fueling gambling addiction with picks and parlays while chastising the Pacers for clowning around on camera at halftime. Though he has plenty of experience making money off the exploitation of hapless proles: at the beginning of June 2025 Shaq agreed to pay $1.8 million to settle a class action lawsuit related to his work alongside Larry David and Tom Brady as a spokesman for the fraudsters at cryptocurrency exchange FTX. To put all of this in perspective, in an oft-cited 2017 study, the National Council on Problem Gambling presents research showing that in addition to high instances of bankruptcy and divorce, gambling addicts have a higher suicide rate than heroin addicts or alcoholics.

Critical commentary on the harm caused by pervasive gambling advertisements throughout the entire professional sports ecosystem may or may not be affected by the blatantly unethical partnerships that the same gambling companies have with TV channels like ESPN and The Athletic, the New York Times sports gambling advertorial insert. An April 2025 story in The Athletic about the negative impact sports betting has on basketball players – they get a lot more death threats now! - begins with the parenthetical disclosure that The Athletic has a “partnership” with one of the largest sports betting companies. “Sports gambling is an important, complex topic,” the sports betting company partner goes on to say, taking a stand on an intrinsically misanthropic and unquestionably harmful industry that is just as spineless as the NYT editorial board’s support for literally every new American war.

Like alcohol and heroin, gambling is not inherently evil. The issue is that vampiric sports betting corporations are more exploitative than ever before, using the mechanics of social media addiction and invasive surveillance tech to help people lose as much money as possible by playing on their phones. “These companies have more data on gamblers than any gambling operation in recorded human history,” says Jonathan D. Cohen, the author of Losing Big: America’s Reckless Bet on Sports Gambling, in an interview with Semafor. He continues,

It seems like they’re using it to identify problem gamblers and make money from them; or identify losers and make money from them, rather than cut off people who have obvious gambling problems and stop them from gambling. This is anecdotal, they claim that it’s all trade secrets, and they won’t give up any of their data. But again, like a tech company rather than a sportsbook, it is their primary resource. Whenever you sign into the app, and you see a customized parlay, that’s like, ‘wow, that looks perfect for me’ — no shit, it is perfect for you. They built it for you.

But perhaps this is a bit too much “inside basketball” for a newsletter ostensibly about slop-style Buddhism and Inter-Dimensional Music, my understandably unpopular but surprisingly long-running FM radio “heavy mellow meditation” art project. It’s just a bummer to see all of these powerful people and journalistic entities taking money that they don’t need from corporations whose profit model depends on driving fans to literally kill themselves, a phenomenon that is simultaneously making the game more unpleasant for the current generation of players. So it goes.

Inter-Dimensional Music FM

Inter-Dimensional Music is North America's Gnarliest Mix of Heavy Mellow, Kosmische Slop, and Void Contemplation Tactics.

I feel as if I have mislead you, dear readers, by prefacing a two-part 10,000 word essay about basketball by telling you that I don’t want to talk about basketball. Although old heads may recall that the most widely-known item from my selected bibliography is “Uncle Skullfucker’s Band,” a similarly long and nostalgic essay about how much I love the Grateful Dead and how I don’t like talking about the Grateful Dead. I appreciate the patience of those of you who have made it this far, and I assure you we are close to the end. But before I wrap things up with a touch of Zen, I am tempted to break another of my promises, and talk about statistics, deep benches, balanced play, and what may or may not be a minor revolution in the way teams win basketball games. . .

ID Music: Dead Sets 2015-2021

I have a complicated relationship with my favorite band, The Grateful Dead. I wrote about this relationship in 2004 for Arthur Magazine, a bohemian culture broadsheet that I had been contributing to for a few years. I was down and out that summer, living in Los Angeles,

. . . But it turns out that I am no more well equipped to convince you that basketball is interesting and the Indiana Pacers and Oklahoma City Thunder are good teams using sports data than I am able to make a case that the Grateful Dead are a good band based on a musicological analysis of my favorite “Scarlet -> Fire” jams.

In addition to charming videos where Pacers discuss their love of baking cookies3 and doing yoga, there are numbers that show how much more often the Pacers and OKC pass the ball, or how much time their bench players – the guys who aren’t the “starting five” – spend on the court, or how they don’t rely on one or two superstars to score all the points. For example, the official NBA account tells us that “The Pacers are the only team in NBA history to have 8+ players average 10+ points per game through the first 5 games of a Finals series!” Sounds like a big deal, but also just look how happy these guys are!

Reading written descriptions of memes is about as enjoyable as reading descriptions of basketball stats posts from online, so here are a few that I’ve pulled from text threads that my wife is on with our homies who are Pacers fans where I usually don’t know what to contribute.

Stats are one thing, but the numbers are embodied in the weary, worn-out faces of titans like Nikola Jokić, Josh Hart, and Donovan Mitchell as they start a fourth quarter after playing almost every minute of the game. Going up against four or five grinning second-string Pacers fresh off the bench: Exhausted heroes with their team’s destiny on their shoulders, risking injury against opponents whose names are only recognizable to the diehard fans who didn’t think twice about adding the Fanduel network to their cable subscriptions back in October.

I know the Dead are a good band because I can hear them smiling at each other through their blunders in a collaborative 30-minute improvisation, knowing that they might stumble through the whole acid-fried mess to faceplant at the end, or they might achieve something transcendent long after the clumsy interlude between “Scarlet Begonias” and “Fire on the Mountain” has faded away.

Likewise, I know the Pacers and OKC are good teams because I can actually see them smiling at each other through their blunders in a collaborative 48-minute session, knowing that they might be eliminated from the series in a blowout, or they might emerge victorious after taking their first lead4 of the game with 0.3 seconds left on the clock.

Even if you don’t care about basketball, it’s still worth watching a highlight reel of Pacers comebacks. The Haliban5 – aka Tyrese Haliburton – makes bonkers clutch-time buzzer-beaters with statistically incomprehensible regularity. But in a testament to the broad distribution of skills across the team, he didn’t take MVP in the Eastern Conference Finals: The award went to power forward Pascal Siakam, whose visage graces bootleg T-shirts sold on the sidewalk outside Gainbridge Fieldhouse emblazoned with the title “Cameroonian King,” and who may be recognizable from many racially . . . complicated . . . “I am the captain now” memes. Or perhaps you’ve seen the viral footage where he appears to be calling on occult powers during the Pacers pre-game prayer circle:

If The Haliban is too soon, Haliburton’s other nickname – The Moment – points to what I like most about the Pacers. Like the Dead’s uncanny ability to slide into gorgeously mind-blowing jams after a shaky, unremarkable first set, Haliburton’s statistically-improbable clutch performances happen because the Pacers don’t get hung up on past mistakes. Haliburton attributes his uncanny ability to slide into gorgeously mind-blowing half-court buckets to playing basketball to play basketball, shooting the ball to shoot the ball. He plays basketball like how I want to watch basketball. Ignoring the commentary, ignoring the score, ignoring past mistakes: In the moment.

Have you ever been in the air so long that your feet begin to fall in love with the new familiar, walking along some invisible surface that is surely there, that must be, as there is no way to describe what miracle keeps you afloat?

- Hanif Abdurraqib

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension

Suzuki was once asked how it feels to have attained satori, the Zen experience of “awakening.” He answered, “just like ordinary, every day experience, except about two inches off the ground!”

– Alan Watts

The Way of Zen

Hanif Abdurraqib’s poetry about Michael Jordan’s ability to soar from the free throw line to the cup has an easy Zen corollary. In an oft-quoted talk, religious scholar Alan Watts recounts an interview where the revered Zen teacher Suzuki Roshi describes the experience of enlightenment as low-key levitation, a metaphor that is too easy to take literally.

While Abdurraqib’s words are almost unbearably beautiful, I’ve never really liked the description of enlightenment that Watts is talking about. It’s a petty gripe, but after living at a Zen center and dealing with guests who are seeking special Zen powers – including a few dopes who swore that they could literally levitate – the analogy of floating through daily life feels misleading, a false promise. The thing about enlightenment is that we’re all already enlightened, we just don’t realize it. “Experiencing life with two extra inches” sounds less like waking up to the reality of the present moment and more like waking up at a shady surgical center specializing in leg-lengthening procedures for incels.

Of the many inspirational Buddhist quotes with dubious attribution that litter online, it’s one often credited to the disgraced Tibetan Buddhist master Chögyam Trungpa that best suits the Pacers:

The bad news is you're falling through the air, nothing to hang on to, no parachute. The good news is, there is no ground.

While I have developed a chip on my shoulder regarding the Pacers that is not uncommon to my Indiana kindred, there is something valid about recognizing the Pacers as perpetual underdogs. The most visible Pacers alum is Reggie Miller, one of a handful of NBA legends – including such luminaries as Patrick Ewing, Allen Iverson, and Charles Barkley – who never won a championship. As part of the Pacers rivalry with the Knicks, Miller had his own rivalry with Knicks fan Spike Lee that resulted in the iconic “choke” gesture that Haliburton mimicked when the Pacers defeated the Knicks yet again in 2025, an image that is popular as a template for T-shirts and tattoos across the Hoosier state.

Miller’s name is also slang for low-quality cannabis, and he is immortalized in Three Six Mafia’s anthem “Stay Fly,” with a verse that also references the aforementioned “choke” gesture. An anonymous annotator at the lyrics website Genius explains it like this:

In summary, 8Ball is detailing how someone who smokes reggie on the regular and then smokes some bomb bud will choke and cough like crazy ‘cause it hits harder.

Miller is now a NBA commentator, and during the 2024 playoff contest between the Pacers and the Knicks the New York crowd launched into a chant of “Fuck You Reggie,” still “not mad but actually laughing” about it 30 years later. Surely no less so now that their championship dreams have been foiled by the Pacers two years in a row. Sure, Miller looks like an age-appropriate dorky dad, but Spike Lee now makes promotional films for the NYPD, and sits courtside at Knicks games looking very “How Do You Do, My Fellow Bing-Bongers?” in a blue and orange ghillie suit.

Watching basketball can be a soothing, meditative experience because I often don’t know what’s happening beyond the visual experience of seeing humans flying and falling through the air. It’s gratifying that the two teams I most enjoyed watching over the last couple of years are now playing each other in the finals. The vibe could only be more positive if The Roots were providing a live soundtrack for the series.

It’s satisfying to understand that the reason I liked watching the Pacers and OKC is one of the reasons they’ve been so successful: their games are compared to track meets, they move the ball around a lot, and they seem to really love playing together. One commentator described OKC as the most fun team for post-game interviews: A star player gets on the mic, but then all of the other players - including their wildly enthusiastic bench – gathers around and the interviewee redirects from his achievements to detailed appreciation of his teammates contributions. Not to get too sappy about it, but both teams are young, good-looking, extremely talented, and they seem to really like each other. Turns out that chemistry translates to good basketball.

I don’t read or listen to much commentary, but I got a lot from an essay that Myles Turner published at the beginning of May, a few weeks before the Pacers victorious playoffs performance, and a few weeks before my 50th birthday. It would be an i n s a n e understatement to say that Turner and I are at very different places in our respective careers. We both left Texas for Indianapolis around the same time, though he landed here as the Pacers 11th round pick in the NBA draft, while I took up residence in a dear old friend’s basement without much of an idea about what I was going to do with my life. Fittingly, this was the same time our paths briefly intersected on yoga mats in the corner of Invoke Studio.

The most useful concept I’ve taken from my slop-style Zen practice is that everything is connected, and nothing lasts, so everyone suffers. Quoting Zen teacher Lewis Richmond, “The fact that we all suffer means we are all in the same boat, and that’s what allows us to feel compassion.”

In “It Took Me 10 Years to Write This,” Turner describes a surprise party thrown for him by friends and family, and the bad feelings that kept creeping in to harsh the good vibes.

The party itself was so fun. But I just kept having this feeling during it — this awful feeling, where I wasn’t exactly sure at first what it was. And as the night went on, it got worse and worse. I tried to shake it and couldn’t. Until finally, I turned to my girlfriend and said it out loud.

“This is amazing. Except … what the f*** are we celebrating?”

You’re not supposed to talk like this, but here’s the truth: I’ve never been an All-Star. I’ve never made All-NBA. I haven’t won a ring yet. Bro, I haven’t even won the division yet. And we got 40-some people dressed up in cowboy hats, celebrating what I’ve accomplished, throwing me a party with balloons??? I almost felt a little embarrassed.

I’ve had my own version of this conversation with my girlfriend – now wife – many times over the last 10 years. My radio show is now on fewer stations than when I started. I don’t sell any of the art that I make. I haven’t written a book. Bro, I haven’t even been able to keep my free yoga classes going.

Turner continues, “Getting out of the darkness wasn’t easy … but the first step I had to take was incredibly simple: I stopped trying to do it alone. I turned to my people […] Sometimes that’s all it takes, belief from your people. So just start there I’m telling you. Anything but isolation.”

Turner’s essay goes waaay deep into the details of his decade as an Indiana Pacer. While I’m still not sure what I’m doing as I start my fifth decade, Turner and the Pacers are one game away from winning a championship and being recognized as the best basketball team on the planet. But in spite of all those successes, he’s been asking the same questions I am, the same questions many of us ask at anniversaries that end in a zero. He answers this question for himself at the beginning of the piece, and he answers the question for me as well.

“Now that I’m deep in it, I think I understand a lot better what it was we were celebrating … and what it is I have to be proud of. And I wanted to write this, because a big part of what I’ve realized — and what means so much to me about my journey — is that it isn’t just 10 years in the league. It’s 10 years in one city. It’s 10 years with y’all.”

Unlike Turner – and unlike my Pacers fanatic spouse – I’ll be just as happy if OKC wins Game 7 on Sunday night. But I’m celebrating 10 years in Indiana and 50 years in this provisional realm of names and forms for the same reason that Turner was celebrating: Because 10 years is 10 years. Because 50 years is 50 years. It hasn’t often been easy, and it has often been dark. But it’s always been anything but isolation.

Everything is connected.

Nothing Lasts.

You are not alone.

The 2025 NBA Finals have been much more stressful than I imagined. I write this the morning after the Pacers tied the series at 3-3, forcing the first game seven since 2016. As soon as I care about who wins or loses, I get distracted from the aerial ballet, like a gambler assessing the odds in the hope of striking it rich or at least not going bankrupt and committing suicide, I begin trying to ascertain whether a team is flying or falling. When maybe it’s both.

While I’d be delighted to see the Pacers take the championship, I’ve spent more time watching OKC, if only because of the punitive delay imposed on local fans. If forced to choose, I’ll go with the Pacers though. If only because Rachel is sincerely emotionally invested in the series, so there is a lot more hooting and hollering while we watch games projected on the wall of our Muncie apartment.

This gives new meaning to the phrase “there’s always next year,” from which Abdurraqib takes the title of his book, There’s Always This Year. And which in turn I am borrowing for this essay appreciating the overlap between Pacer nicknames and Zen concepts: “There’s Always The Moment.” As the 2025 season comes to a close, this means looking forward to the first games of a new season in October. Resuming the meditative practice of watching the games to watch the games, staying free of preferences for good and bad. To celebrate basketball because it is basketball, and it is something joyful to witness in a world that seems to have turned its back on compassion and kindness and all of the things I value most in life.

It’s a way of enjoying basketball that is best explained, once again, by Myles Turner. In a post-game interview the person holding the mic asks him one of the usual meaningless, koan-like variations on “what was the biggest challenge in this game.”

His response is an unassailable truth that has the clarity of satori, an answer like an empty ball ringing above the rim. It’s also the reason that I enjoy watching basketball games: “Everyone out there is an NBA player.”

The Indiana Pacers meet the Oklahoma City Thunder for Game Seven of the 2025 NBA Finals on Sunday, June 22 at 8:00 pm ET.

Vøid Contemplation Tactics is free to anonymous lurkers, but if you’d like to make me feel better about the time and energy that I put into producing this newsletter, you can subscribe for free and give me a welcome hit of dopamine. Or you can subscribe for money and help me feel guilty about not sending newsletters more often!

You can also drop a one-time donation in the tip jar.

It’s also super encouraging when you share this with your nice friends. Regardless, thank you for being here.

Congratulations if you don’t know that this is a white supremacist number pointing to “the fourteen words” which is a sentence about protecting the future of white people and H is the eighth letter of the alphabet so you can guess what these dipshits mean by H H. Sorry.

As one politics person on Blue Sky posted after The Moment scored an incredible game-winning shot the same night that a war between India and Pakistan appeared to be starting, “I was so confused why so many of you were suddenly posting about Halliburton!”

sorry not sorry; image via r/NBAEastMemeWar

Another Indy Zen dude her to say, this reads like Chili on the next solstice. Keep up the great work long after Sunday!

We used to call that no-rules style "animal basketball" at recess in my 99% white catholic school.

When the year 2000 is invoked regarding the NBA I have SEVERE PTSD. Watching the Blazers 4th quarter meltdown in game 7 of the Western Conference Finals was one of the most traumatic events that don't really count as a traumatic event. I still remember the pitcher of bloody marys I made using martha stewart's recipe, my mom's congratulatory call from NJ to Portland at halftime... that proved to be a major jinx, and the hoop I set up in my backyard before the game as being cursed.

I assume you saw PE is touring with GnR?