There's Always This Moment I

Talking and not talking about basketball, Zen center life, barber shops, and reggae

Years ago, shortly after accepting a position at the University of Kentucky, my history professor brother confided in me that his resurgent interest in basketball – and to a lesser degree, bourbon – came out of a necessity to have something to talk about at parties. His academic specialization of “twentieth century international history with a focus on U.S. foreign relations and the Middle East” could conceivably lead to more complicated conversations than “how about those Wildcats” and is only slightly more sensitive than his defense of Wild Turkey 101 – which is about 102 more Turkeys than I care to consume – as the top-ranking American whiskey.

He’s at Columbia now, and we don’t talk very often, but I can imagine that the whiskey guy debates over the aristocratic transcendence of Pappy Van Winkle versus the earthbound tasting notes of Wild Turkey are less fraught in Manhattan. Given the current political climate when it comes to objecting to US support for Israel’s ethnic cleansing campaigns targeting Palestinian refugee camps and hospitals, I can also imagine he has thoughts prepared on the Knicks recent playoff performance. Although his third book – Scorched Earth, a 656-page “global history of World War II” – was published in early May, so that should give him plenty of material for light conversation.

A “sports talk” option could be similarly useful to someone such as myself. Small talk stresses me out much more than intimate conversation: A group chat about what we’re watching on TV this week is waaay more uncomfortable than talking about dying parents, or what cocktail of head meds my fellow middle-aged “creatives” are using to moderate the surges of depression and anxiety that make us think we’re failures. But talking about basketball is like talking about Buddhism: my slop-style beginner’s mind means I get lost quickly when the conversation requires familiarity with the Pāli Canon or “zone defense.”

ID Music: Astra Taylor

On distinguishing the “existential insecurity” inherent to human life and the “manufactured insecurity” that is gives rise to so much preventable suffering in the present moment

Outside of the existential insecurities that affect everyone living in an impermanent realm – regardless of their financial situation – the older I get, the less I have in common with my Generation X cohort. I don’t have kids, and don’t own property. I have two nice cats and watch TV but I get bored quickly talking about cats or TV. I read a lot of sci-fi and horror paperbacks – the real nerd shit more often than not – but you probably don’t. I listen to obscure and sometimes unpleasant music made by people half my age that is often unavailable on the streaming platforms that are the sole source of audio entertainment for 95% of the people I know.

It’s good for a laugh to respond to the Gen X Guy prompt “I’ve been revisiting The Replacements discography, what have you been listening to lately” by talking about Texas metal band Pyramids and their new album’s surprisingly successful blend of black metal, shoegaze, and reggaeton. “Ha ha ha” but soon they’re heading back to the buffet for more spinach dip and I’m looking for the bathroom and feeling weird about all of the unmonetizable, conversationally useless knowledge I’ve acquired over the last 50 years. As a fellow middle-aged music weirdo friend from online once posted, “Whenever people ask me to DJ at a normal party I reflect on how much time and money I’ve spent collecting some of the most unlistenable music ever recorded.” Sadly, it seems unlikely I’ll be finding a publisher anytime soon for Scorched Vibes, my 656-page inter-dimensional history of DJ Screw’s influence on contemporary vaporwave.

Liquid Advertisement & Gaseous Desire

A vaporwave supersession featuring the Inter-Dimensional Music debut of Jacques Derrida and screwed & chopped Smokey Robinson

I don’t really know if I have a job, so the question “what do you do” from one of my wife’s colleagues – Rachel works at Ball State’s art museum – at a reception is followed by an awkward pause as rising shame vapors begin to cloud my vision. “Depends on the time of day ha ha” is a go-to if I don’t want to explain that I’m an artist whose projects are mostly paused, and my medium is “yoga and slow-motion water videos.” Or that I write a free newsletter about Inter-Dimensional Music, my ambient/metal/meditation/reggae FM radio show that airs late on Sunday nights in Far West Texas on Marfa Public Radio, but is actually usually Luddite ranting and hopelessly naive anarchist interpretations of Zen.

At the very least, the “homemaker” title that the bank awarded me when we set up our joint checking account a few years ago is a reminder of my highly specialized Zen training in cleaning unintentionally low-flowing meditation center toilets, sweeping cat litter from the dharma room floor, and policing commune kitchen hygiene. But it will always feel like I’m stealing valor from my mom, and people don’t take me seriously anyway, given the gender inversion and the fact that we don’t have kids.

Perhaps as a result of the financial repercussions of “I haven’t been able to say what my job is for 10 years,” my politics have also become more uncomfortable to talk about with many other fifty-somethings. Rather than the stereotypical but hardly inevitable middle-age slide toward conservatism that often accompanies the attainment of a professional salary or a transfer of life-changing generational wealth – that exceeds the safety net of middle-class1 generational wealth that gives me a modicum of stability – I’ve gone from “I’m an anarchist and not a communist because I like listening to Crass more than I like reading Gramsci” to “Crass still slaps, but also Mao had some interesting ideas about landlords ha ha.” Nevertheless, before making an entrance to many social gatherings, I will often ask my wife to avoid mentioning that I watch a lot of basketball.

In my never-ending search for an answer to “what do you do for a living,” I’ve been researching Zen chaplaincy training. I was looking at a program offered at the Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico and getting excited until I figured out that the mostly-online two-year course came with a $13,200 price tag. This seems like a lot to pay for a series of interactive webinars that results in a certificate qualifying the bearer for a job that probably doesn’t pay much! Especially if you’re working outside of premier venues on the hospice circuit. In comparison, two years of in-person tuition at the community college here in Muncie comes in at around $10,000, and results in a more lucrative certificate in dental hygiene or automotive technology. At 50, my vocational aspirations are looking more like a “Zen or the art of motorcycle maintenance” type of situation.

The chaplaincy training tuition corresponds with some of Upaya’s other public programs, including $500 registration fees for two-day Dōgen seminars and calligraphy workshops. This is fine – even if you’ve paid off the temple mortgage, providing the sangha with all that fermented bean curd and mint tea isn’t free. That being said, their residency program is considerably more affordable: $900 for the first month, $100 after that, and free after six months. The price of living at a Zen Center is often better measured in the limitations – and frustrations – that make it such a profound learning experience, which makes the Dōgen workshop seem like a bargain. You might not be paying rent at the dharma center, but living there isn’t free!

As with art, music, or sporting events, the price of admission is an indicator of who the experience is for. This is less about Upaya – a place that has a reputation for socially-engaged Buddhism, and is led by the highly regarded Roshi Joan Halifax – and more about how living at the exponentially less refined Indianapolis Zen Center – a borderline apostate2 religious community in the Kwan Um School – led to my own resurgent interest in basketball.

Editor’s note: Both residency programs are good examples of the significant differences between the camouflaged gentrification of “artist community” housing, co-ops, and actual practicing communes. A topic that we expounded on at length in this previous installment of the Vøid Contemplation Tactics newsletter:

The Rent Is Always Too Damn High

Utopian housing dreams versus waking commune life in the Midwestern United States

“To live in a [Zen Center] community is not easy,” Zen Master Wu Bong, a teacher in the Kwan Um School says in “The Practice of Together Action and Buddhist Wisdom,” a 2008 dharma talk. “There is a structure and a set of rules that must be followed,” he continues. “There is less privacy than one would have living outside such a community.” Showing up for meditation practice at 6:30am can be a problem even if it just means walking downstairs. But the challenge that drove me to drink came from the kitchen. As Wu Bong gently puts it, “There is sometimes food one does not like, and often a lack of food that one likes.”

We all took turns at preparing meals at IZC throughout the week, but the advantages of “beginner’s mind” in the dharma room are not the same as “beginner’s mind” in the pantry. I was not totally exempt from dinnertime SNAFUs: While I prided myself on spiralized primavera veggie pasta and vegan curries served over roasted cauliflower rice, I also shamefully sprang for takeaway mezze platters, fighting back tears of frustration when my poorly-made falafel balls dissolved in a boiling pot of canola oil.

On nights when the resident cook was too depressed or ignorant of basic culinary skills to come up something more than, say, a can of chunky vegetable soup served over macaroni boiled into wheat paste, I would ride my bicycle a couple miles up the street to the Red Key Tavern. I ended up there at first because it was the closest place to the Zen Center where I could sit and stare off into the distance, when sitting and staring off into the distance at the Zen Center became too hectic. It was an unconsecrated dharma room that offered profane sacraments of meat and booze along with quiet contemplation. The bartenders knew my order but not my name, so I felt welcome without the pressure to socialize. They did know enough to appreciate that I was hiding at the bar like some kind of dirtbag dharma dad, seeking refuge from my spiritual family’s disappointing dinner offerings.

It wasn’t long before I figured out that this unassuming dive was one of Indianapolis’ most beloved and long-standing bars, once frequented by Kurt Vonnegut, and was counted by Esquire in 2011 as one of the best bars in the US. Perhaps because the place hadn’t changed much as a result of these accolades, it was usually quiet on weeknights. I’d sit at the end of the bar next to the jukebox stocked with World War II-era 45s and closest to the silent TV that was often tuned to basketball: With 30 or so teams playing a regular season of 82 matchups, there are somewhere around 1240 games happening between October and April of any given year. I didn’t have loyalties to specific teams, but I saw enough local games to recognize that the 6’11” guy with short dreads that I sometimes sat next to in the furthest corner of yoga class was Myles Turner, who was playing his second year of NBA basketball with the Indiana Pacers. Turner and I never spoke to each other, but we were both downward-dogging on the floor of Invoke Studio for at least one of the same reasons: As Turner says in an interview about his years of dedicated yoga practice, “It’s so much better not doing it on your own.”

If there is a discomfort that registers, perhaps it is in the realization that, once again, there is a code that they cannot decipher, no matter their desire to. No matter how many times they have fallen into dreams of our language, our enemies wake up with the same tongues, reaching but falling short. What else to do, then, but to imagine every gesture toward flyness as an affront to their own monochromatic living?

- Hanif Abdurraqib

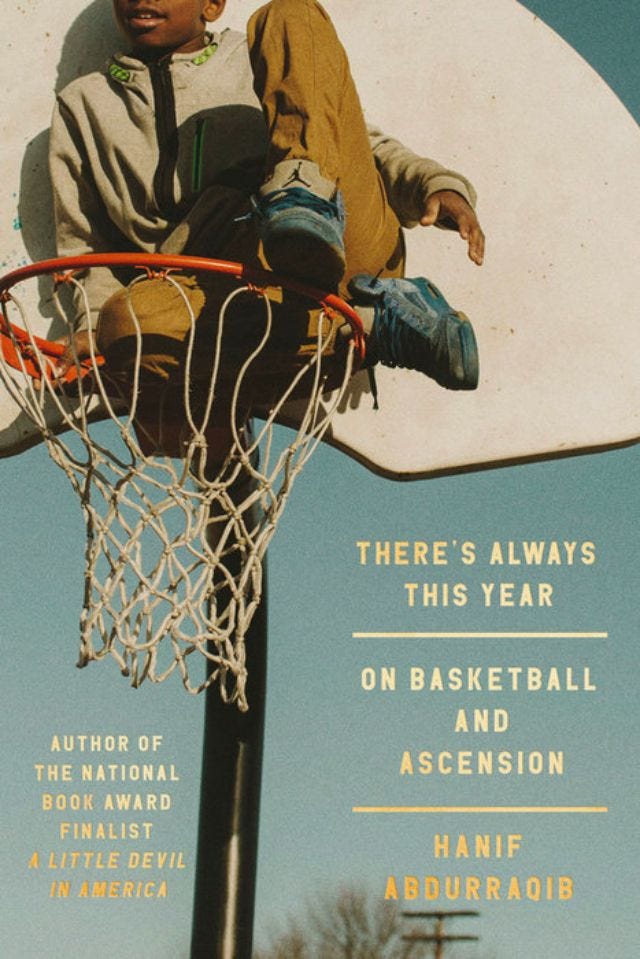

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension

There is much to be said about the form and function of professional basketball players – from Hanif Abdurraqib’s poetic descriptions of Michael Jordan’s early appearances in slam dunk contests, to the corny technicality of ESPN’s animated AI-slop post-game analysis of every shot taken by Oklahoma City point guard Shai Gilgeous-Alexander in the 2025 playoff series. But as a wide-eyed late-coming middle-aged basketball dilettante, my thoughts on the mental strategies and physical mechanics of the game are naive at best, clumsy and incorrect at worst. Trying to keep up with real basketball heads can be as embarrassing as my analysis of Rastafarian poetry in freshman English at a 99% white high school in Zionsville, Indiana circa 1989.

This was the pre-internet era where ascertaining the lyrics meant rewinding-playing-rewinding-playing-rewinding Legend in my cheap GE-brand “walkman” until I decided that Peter Tosh’s verse on “Get Up, Stand Up” was “We're sick and tired of your easy kissing game” rather than “your ism and schism game,” a mishearing informed by the harsh moral teachings on premarital sex from the Christian Nationalist church that my parents dragged us to each Sunday morning. I was mostly ignorant of Iyaric’s fluid linguistics, completely missing the dread talk critique of those same right wing spiritual and political ideologies (isms = easy) as vectors for discord that reinforce false binaries (schisms = kissing). Referring to the Detroit ‘76ers in 2025 is less charming. As I mentioned earlier, casual conversation about basketball is full of pitfalls, and very stressful. Talking about Rastafarian semiotics and using the correct pronunciation is comparatively easy as long as we crazy baldheads follow the rule from I Think You Should Leave’s “Hat in Court” sketch: Don’t do the voice.

I am only slightly more knowledgable in talking about the hair styling that is a big part of what I enjoy about watching basketball. Ironically, I was educated on the semiotics of such flyness because I am a white baldhead. Prior to my return to Indianapolis in 2016, I lived in remote Far West Texas, a literal as well as metaphorical desert in terms of ecology, medical care, nutritious food, and quality barbering. I relied on the assembly-line clipper operators in barbershops near Fort Bliss, pit stops when running to or from the El Paso airport. One of these Wahl techs was the first to gently break it to me that I’d reached the point in life where I needed to start trimming my eyebrows and ears more often than the increasingly sparse hair turning from brown to gray atop the Sunburned Dome of the Chambo.

My hair game changed forever after returning to the Midwest, when I saw a mural on the wall of Carols and Everybody’s Barber Shop while walking around my new Indianapolis neighborhood. The shop’s door was locked, but I heard voices and knocked politely. I was seeking a quick trim before a family portrait for Mother’s Day. As long as there was someone inside who could get the hard-to-reach spots on the back of my large, thick skull, I’d be good.

A young Black kid opened the door, and was pretty obviously not expecting someone who looked like an out-of-shape extra from Green Room. It was clear from a glimpse inside that this was not just an establishment run by a Black barber, but a double capital-B Black Barbershop, full of comfortably-lived-in clutter, chess boards, posters with meticulously rendered technical diagrams of Black hairstyles hanging on the walls, and a mini-fridge that might’ve been stocked by Allen Iverson3. We both paused, but it occurred to me that the weirder and ruder thing to do would be to say “sorry, my mistake” and scoot down the block. “Do you sell haircuts here?” I asked, which was weird but hopefully not rude.

The kid looked me up and down again. “Marvin! There’s a . . . guy here,” he said, and closed the door again. A week later at the family portrait session my mom proclaimed the freshly faded sides of my skull and the precision lines in my beard to be the best haircut I’d ever received.

Though they offered braids and perms by appointment, Marvin was the only barber working at Carols and Everybody’s, and I only came back at his invitation. He was a very large man with an impeccable brutalist head of hair and massive beard, all the more impressive for its topiarian symmetry. He wore plain black T-shirts, black LA Dodgers snapbacks, and had a detailed tattoo of a pair of clippers on his forearm. We were the same age, though we grew up in very different circumstances: He was proud of being from the north side of Indianapolis, and I was ashamed to admit I was from Zionsville, a white flight suburb and “sundown town” north of the city. Technically I grew up in the country in between Zionsville and . . . Whitestown . . . but that detail didn’t do me any favors.

“To this day, African Americans who know about sundown towns concoct various rules to predict and avoid them,” sociologist James Loewen writes in Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, his history of the “organized jurisdiction[s] that for decades kept African Americans or other groups from living in [them], and were thus ‘all-white’ on purpose.” The name comes from signs posted at the edge of town advising Black people to be on their way before nightfall in much more violent language. Circumventing towns with colors in their name is one of the general guidelines for Indiana, even if the color is black or brown.

While Loewen makes the case that “more than half” of all towns in Indiana, Oregon, Ohio, the Cumberlands, and the Ozarks were – and in some cases, still are – sundown towns, I grew up in an interstitial rural zone in between a working class sundown town and the more insidious upper middle class manifestation in Zionsville. “Residents of all-white suburbs also usually avoided the term, though not the policy,” he writes.

Marvin and I ended up talking about hip-hop because he was kind enough to seek out generational common ground: Neither of us grew up with cable so instead of BET or MTV, we relied on the janky pay-to-play video channel The Box to discover now forgotten rap songs like Cool C’s “I Gotta Habit.” We both tuned into WTLC, Indy’s local R&B station, late at night hoping to catch the rare appearance of De La Soul or Special Ed in the mix with Michel’le and Babyface. It didn’t hurt that he halfway remembered URB, the Los Angeles-based hip-hop and dance music magazine where I worked in the late ‘90s. I talked about Above The Law and Freestyle Fellowship and he quoted Mac Dre and Z-Ro. But mostly I got invited back because I knew when to be quiet. I was thrilled when Marvin tagged me into barbershop rap chats saying “Daniel’s old school, like me.” But I knew I had nothing to add when the conversation turned to basketball.

Marvin eventually moved on from Carol and Everybody’s after the owner declined to sell it to him, an emotional decision that we talked about at length. “Black men of a certain age carry large keychains with great pride,” he explained. “Owning property is not something they will ever take for granted.” I followed him to his new shop, All in The Wrists. Along with the Red Key, the barbershop was a community space where I could escape from the stress of Zen Center life. Marvin hired a couple other barbers, and while occasional goofy stories of life at a Buddhist commune were welcome, it was also a place where I could sit and stare quietly at the floor or the posters on the wall.

I understood that access to All in the Wrists was a privilege every time I walked in the door and the room would fall silent, all eyes on me. “Daniel!” Marvin would bellow, raising his hand in greeting. “Find yourself a seat.” And conversation would resume. I asked Rachel about this once, worried that I was thoughtlessly trespassing in a Black space, doing the white man thing of presuming I can barge in and be welcomed wherever I please.

“You can’t get an appointment unless you call Marv on his personal cell phone, right?” she asked me. “Do you think the guy with the clippers tattooed on his arm that everybody refers to as ‘OG’ would be reluctant to make you feel less than welcome in his shop?”

The Black barbershop experience is the most luxurious grooming experience I’ve ever experienced. The only distant contender being a salon in Los Angeles where they served me weed brownies – in the good old days before Prop 215 – because I was pals with the owner. Marvin took a few snips with his rarely used scissors up on top, but it was mostly graceful movement of various clippers skimming over my head, steady and confident, my pale scalp protected by each carefully selected guard. Then a hot towel, beard oil, and whatever Black hair products that OG deemed culturally appropriate for a repentant white devil such as I.

It was in this setting that I listened to Marvin and the other barbers’ war stories of weekend hair battles: public barber expos and raucous competitions where they tested their skills in creating ornate designs on stage with complex props, DJs, and cheering audiences. “Can you do the Prince symbol in the back of my head?” I asked when there was a long enough pause.

“No.”

“What about Batman?”

“Daniel.”

And that was as all it took for me to settle back into listening mode.

These exchanges triggered fond memories of the similarly generous Black friends who – in my youthful days of long hair, after I’d explored Rastafarian music beyond what greatest hit collections Columbia House had to offer – explained patiently but firmly that tangling my hair into scuzzy dreads was a bad idea, regardless of how much I admired fermented crust punk locks. “Nausea and Sepultura are not the same thing as Bad Brains or Mutabaruka,” they’d remind me. I might’ve protested at first, but the same gentle yet curt “Daniel” would always finish the debate.

“This idea that what is atop the head or not atop the head or what is temporarily masking the head is all a language, a code,” Abdurraqib writes in the beautiful basketball memoir There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension. “That at the highest point of the body, there is still a point that can be made to ascend higher, by some invention of whatever God has given us to design with, or whatever wasn’t given, or what was given once and taken away.”

It was only by the grace of what was given once but taken away – my flaxen hippie cosplayer mane, unfortunate man buns, french braids woven by cheerleader crushes in high school, and Willie Nelson-style headneck locks – that I was gifted an abridged outsider’s knowledge of what Abdurraqib refers to as “the language of Black hair.” Since I was losing my hair, there wasn’t much left to appropriate: I wouldn’t have made it past the door with a patchouli-fertilized nest of matted wook dreads.

This opened up a new way to see basketball, and to understand how much of a difference it makes to watch a sport where the heads are unfettered by helmets. It’s an opportunity to appreciate the language expressed by Oklahoma’s Jalen “J Dub” Williams’ flip from floppy afro and goofy grin at photo shoots to tightly lined braids and cold-eyed gaze on the court. To feel admiration but not envy for Oklahoma’s other Jaylin “J Will” Williams’ perfectly twisted dreads. Or to nod wisely at the synchronicity between Myles Turner’s dreads flopping on the side of his head, tucked under the white NBA headband; and the “business in the front, party in the back” style of braids tucked in a similar style under fellow Pacer Andrew Nembhard’s headband. I can also hazard a guess as to which white players understand the importance of a barber who can put a line in before a game, or keep a creeping neck beard in check. I always rolled solo to appointments with Marvin, but I can more easily imagine showing up with Pacer TJ McConnell than Cavalier Max4 Strus.

Like with so many things in basketball, it’s Rachel who has helped me better understand the semiotics of basketball hairstyling, a conversation that begins with fond recollections of her favorite player’s inspirational braids thirty years ago. “While men like Dennis Rodman broke barriers with beauty in sports, a then 26 year old Iverson became the first in NBA history to have a braid appointment mid-game,” India Espy-Jones writes in Essence. “A reminder of just how important hair is in the Black community — and how beauty often teams up with our success.”

This is also an excuse to draw your attention to the secret archive of vintage games – the full games – available on NBA League Pass. There are dozens of pages dedicated to stars like Iverson along with individual team pages including highlighted contests ranging back to the ‘70s, but as far as I can tell they’re not cataloged anywhere on the site. I only discovered this by messing around with the direct link, successfully surprising Rachel at the end of a rough day by dialing up The Answer’s 1996 NBA debut. . .

Continue reading in “There’s Always This Moment II” featuring Guns N’ Roses, sundown suburbs, and an unexpected pivot from Allen Iverson to Alan Watts.

There's Always This Moment II

This is the second part of an essay about basketball, Zen, reggae, hairstyles, and sundown towns, among several other things. It will make more sense after you read the first one, which you can find here:

The Indiana Pacers meet the Oklahoma City Thunder for Game Five of the 2025 NBA Finals Monday, June 16 at 8:30 pm ET.

Vøid Contemplation Tactics is free to anonymous lurkers, but if you’d like to make me feel better about the time and energy that I put into producing this newsletter, you can subscribe for free to give me an welcome hit of dopamine. Or you can subscribe for money and help me feel guilty about not sending newsletters more often!

You can also leave me a one-time donation in the tip jar.

It’s also super encouraging when you share this with your nice friends. Regardless, thank you for being here.

My parents are extremely equitable when it comes to me and my brother, so they started giving me a monthly deposit roughly equivalent to the money that my brother was saving on childcare by sending my nieces to Mam-Oh and Bah-Poo’s house after school.

As the IZC’s crusty octogenarian dropout OG guiding teacher says of many of the Buddhist early adopters he came up with in the ‘70s, “Oh I’ve got stories about Roshi Joan.” Sadly, telling tales outside of the temple is strictly forbidden but one time I offered an edible acquired legally in California to the same teacher and when I warned him to “be careful it’s kinda strong,” he misunderstood me and I had to disappoint him by explaining that I was not passing him a peyote button.